Economy

IPA’s weekly links

Guest post by Jeff Mosenkis of Innovations for Poverty Action

Claudia Goldin charts a century of women in the workforce

- I’ve heard these days in medicine there’s a glut of papers that are all essentially “[thing I was doing already] + in the time of COVID,” which seems like is true of all fields now. The German Development Institute for Evaluation (DEval) has a helpful roundup of several useful new hubs for evidence, research, and methodology resources for dev/social science.

- A few weeks ago I saw someone say something like “good thing economics is so status driven and hierarchical, at least someone gets to publish nulls.” Heres’s a nice thread of responses to Pia Raffler’s request for resources on showing (and publishing) null results.

- Stefano DellaVigna and Elizabeth Linos compare the size of effects in academic trials of nudges, to 126 RCTs conducted by Nudge Unit trials in the practical world:

“In papers published in academic journals, the average impact of a nudge is very large – an 8.7 percentage point take-up effect, a 33.5% increase over the average control. In the Nudge Unit trials, the average impact is still sizable and highly statistically significant, but smaller at 1.4 percentage points, an 8.1% increase.”

They find publication bias and statistical power account for the difference (perhaps some nudge researchers can read the responses above for how to publish disappointing findings). Then using forecasts, they find academics overestimate the effects an intervention will have, while Nudge Unit practitioners are accurate.

- How are you at forecasting? A new prediction platform spearheaded by DellaVigna and Eva Vivalt lets anybody sign up to predict the outcomes of several trials.

- This is why we can’t have nice (or cheaper) things. The Times has an exposé of an institute at George Mason Law School funded by big tech companies who happen to be under regulatory scrutiny (h/t Florian Ederer.) The institute they fund trains regulators in the school of economic thought that the best kind of regulation is as little as possible. It follows the model of a judge training institute that does the same thing, and has been shown to influences judges to rule in favor of mergers. Planet Money had a couple of really good episodes explaining why, for example, we have only a few big telecom companies. It comes back to Robert Bork (Apple) taking an econ class at UChicago in the 70’s when he was in law school, and writing a book for the law field explaining that economics says to leave markets alone. There’s another good episode (Apple) on what this means for the big tech companies today like Google and Facebook. In summary, your cable and cell phone bills are so high because a dude took an econ class in the 70’s, and that’s the butterfly effect.

- For a counterexample, see Michael Lewis’ podcast episode “Baby Judge School,” which trains judges to be aware of their own biases and how to counteract them more effectively (Apple).

- An uncomfortable truth is that academics are big polluters, through conferences and other kinds of travel, but many of us are figuring out how to accomplish similar academic events without the travel these days. Here’s a really interesting article on how to de-carbonize conference travel, through simple things like holding them in more central locations, and having simultaneous regional hub meetings that connect to one another digitally. One crazy statistic, they calculated the carbon from travel for one major scientific conference and found on average it was “about 3 tonnes per scientist, or the average weekly emissions of the city of Edinburgh, UK.”

- Happily the NBER Summer Institute this week was online and therefore open to far more people. Claudia Goldin gives the Martin Feldstein lecture at NBER Summer Institute on women’s career progress over a century. “Tammy Duckworth is the first senator … to bring a baby into an active session of Congress, though many would say there have been babies in Congress before that time”

The post IPA’s weekly links appeared first on Chris Blattman.

Economy

Fear & Data

Fear.

It is a key driver of behavior, whether in markets (Fear & Greed), politics (Tribalism), Health care (Anti-Vaxxers) or whatever (FOMO).

Fear is a great memory aid. For most of human history, people communicated not via the written word, but by oral storytelling. Hence, we are primed for emotional, memorable narratives. Looking at data and performing cold, calculated analyses is a learned, not innate, skill.

Social media understands this. Is it any surprise the algorithms of Facebook surfaces the most extreme views and claims? Look at what plays directly into that evolutionary trait, via clickbait and manufactured outrage. With our perfect hindsight bias, isn’t it obvious how inevitable this was?

Irrational fear is a driver of much of what we think and do. Often reflexively, frequently without thought. Contemplate what this means as you process new pandemic information, relying on mental models, performing data analysis.

How often do we react to a headline we disagree with, but after diving into the data underneath, it changes our mind? Not often enough, but on those rare occasions when that happens, it is a sign that you are doing this correctly. Our first reaction is the thoughtless programmed emotional response; the second is the more complex analytical result. It is your lizard brain (basal ganglia and brainstem) versus developed frontal lobe (neocortex).

Which brings us back to Covid-19. The probability of anyone of person getting this disease and then suffering a fatality is exceedingly low. I don’t want to suggest things are statistically normal, and you should definitely do things to stay safe: wear masks, socially distance, wash your hands frequently, and not touch your face. You can be (relatively) safe by doing these simple things.

But excess fear is driving all sorts of negative consequences, including stress, psychoses, economic damage, relationship issues, and health problems. This is counter-productive.

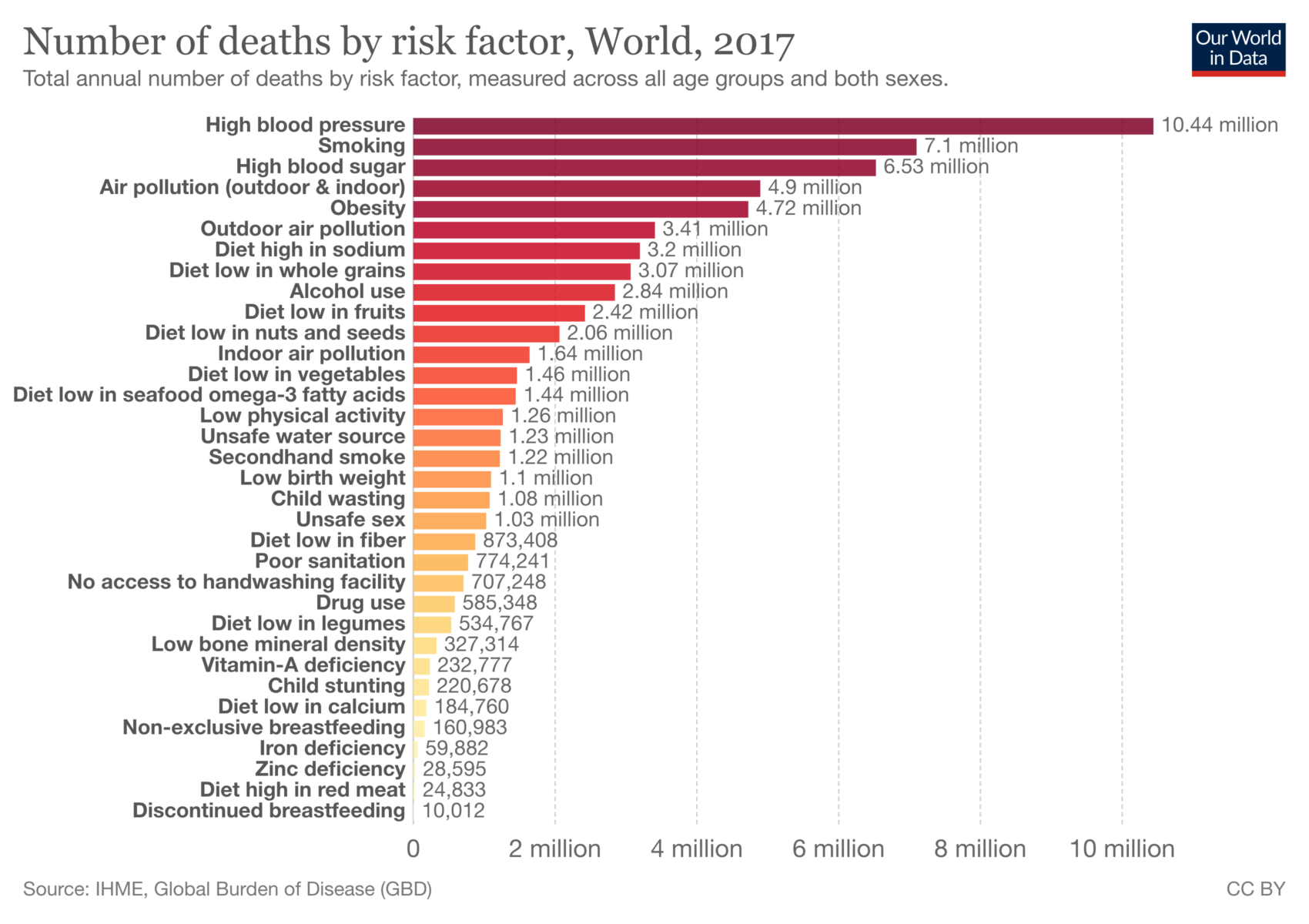

One day, this pandemic will end. Then we can all go back to worrying about cholesterol, high blood pressure and sugar.

Previously:

Over/Under Represented: Causes of Death in the Media (June 13, 2020)

Fearing the Dramatic, Complacent for the Mundane (April 29, 2020)

Denominator Blindness, Shark Attack edition (February 5, 2020)

Shark Attacks Illustrate an Investing Problem (February 4, 2020)

MiB: Danny Kahneman (February 11, 2020)

Crashes & Terrorists & Sharks – Oh, My! (November 9, 2020)

How’s Your MetaCognition? (August 16, 2020)

Source: Our World In Data

The post Fear & Data appeared first on The Big Picture.

Economy

COVID-19 Tearing Families Apart

COMMENT: Mart, this is tearing my family apart. I can no longer even speak to my son. He is against Trump simply because he does not like him personally or his tweets. I try to explain this should not turn on those issues. This is a war for your future. My son will not listen and he will vote against himself and is too brainwashed to see the bigger picture.

GA

ANSWER: I know of many people in the same boat. Even two of my business partners had ended all communication with their children. My partner, who died about 20 years ago, insisted I make sure everything went to his second wife and nothing to his children in the event of his death. These things are sad, but the brainwashing that has been taking place is thicker than even blood. It is very sad. But this is precisely what was carried out in East Germany. They deliberately tried to turn the children against their parents. That was a strategic tool of the left. This entire COVID-19 scheme is dividing the country. One father wrote in and said his son said all he cared about was taxes. They have no idea what their vote will mean in this election.

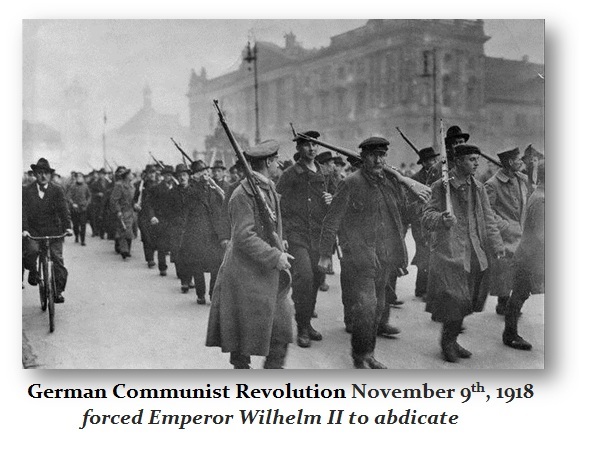

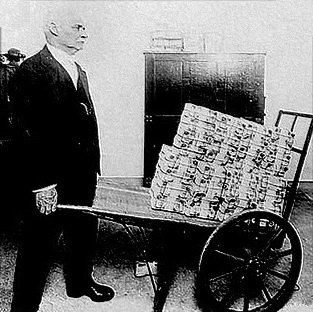

This is an agenda that is well organized, and it is a major effort as was the Communist Revolution of 1848 and then 1917/1918. People know about the Weimar Republic and the hyperinflation of the 20s, but it was a revolution in Germany in 1918 that overthrew the government, even boldly asked Russia to come to absorb Germany so they could enjoy the Communist Utopia, that led to the chaos. People hoarded all wealth and converted to foreign currencies.

This is an agenda that is well organized, and it is a major effort as was the Communist Revolution of 1848 and then 1917/1918. People know about the Weimar Republic and the hyperinflation of the 20s, but it was a revolution in Germany in 1918 that overthrew the government, even boldly asked Russia to come to absorb Germany so they could enjoy the Communist Utopia, that led to the chaos. People hoarded all wealth and converted to foreign currencies.

The idealistic fools who were brainwashed were left penniless. This is the fate of your son, sad to say. Those with any wealth, the older people, understood what was at stake. They prepared. The youth, believing in Utopia, suffered from hyperinflation. When the new currency was finally created in 1925, it was backed by real estate — not gold which had vanished thanks to hoarding.

Unfortunately, the youth are blind. Biden is a puppet. He will surrender the sovereignty to the United Nations and this is why they are fighting so hard. Michael Bloomberg is very evil. He is trying to pay all the fines, $20 million, of felons in Florida with the implication they will vote for Biden. I really do not want to live in a world where Bloomberg has any power whatsoever. The nice things will be to see Gates, Zuckerberg, and Bloomberg, among a long list of others supporting this new tyranny, will then become the targets are stripped of their wealth as the final phase takes place — nationalization of companies.

There is nothing you can do. They have been brainwashed. It is hard to bear. But we simply must understand that they are creating this new world and they will ONLY learn from experience. We cannot shelter them. To walk, they have to fall many times. This can be irreversible. Unless they see the error of their ways soon, then the split becomes permanent. The more you try to show them, the more they will not listen. That’s why it is so important to pay attention to what they are being told in school.

Economy

A Partial Defense of Milton Friedman’s 1970 NYT Essay

To understand my story, you first need to understand Friedman’s basic point. Here it is in a nutshell: Managers are employees of corporations. In the decisions they make with corporate resources, they should be responsible to the corporation. That means being responsible to the stockholders, who, after all, are the corporation’s owners. The vast majority of stockholders want the corporation to, in Friedman’s words, “make as much money as possible.” Thus Friedman’s claim that the social responsibility of a corporation is to make money. Friedman was clear that he wasn’t advocating breaking the rules. He stated that the managers should conform “to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.”

I learned Friedman’s point in a personal way when I was eleven. My mother had raised us to help others. I liked doing that and didn’t see it as a heavy obligation. But when I was eleven, my brother, Paul, who was fourteen, bought a cheap set of golf clubs and hired me to caddy for him. When we were on the eighth hole of a nine-hole course near our summer cottage in Minaki, Ontario, we saw a golfer hunting in the rough for his lost golf ball. I thought I should stop and help, so I did.

Paul had a different view: he wanted to play through and I was working for him and so I should do what he asked. We had a big argument and I finally gave in. When we got home, my brother complained to my mother that I hadn’t kept my side of the bargain. I was sure my mother would support me. She didn’t. “When Paul hired you,” she said, “you were working for him. When you’re on your own you can stop and help someone find his ball, but when you’re working for someone, he has the right to decide whether to let you.”

The lesson stung, but I ended up agreeing. That’s why the most important part of Friedman’s essay spoke to me. It’s simply wrong, when you’re working for someone, to use his resources for your ends when they don’t promote his ends. In the case with my brother, I was using my time to help others but my time was really his time: he was paying for it. In the case of corporations, managers might be using both their time and the corporation’s resources to help others even though shareholders own those resources and own the manager’s time that they are paying for.

This is from David R. Henderson, “Friedman’s Critics Miss the Mark,” Defining Ideas, September 24, 2020.

I was one of the 20 people asked to comment on passages of Friedman’s famous 1970 NY Times essay, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. Hoover colleague and EconTalk host Russ Roberts was another.

One of the strangest comments was by Felicia Wong. I write:

Commenter Felicia Wong, president and CEO of the Roosevelt Institute, notes that Friedman wrote when America’s “overwhelmingly white” fears were about Watts, Detroit, Vietnam, Kent State, Jackson State, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. Hmm. I recall that when King and Kennedy were murdered a lot of black people were upset, too, particularly by King’s murder.

I did note an irony in Friedman’s original essay though:

I’ll end by noting an ironic argument in Friedman’s essay that I don’t agree with and I wonder if even he would agree with today. Fortunately, it doesn’t undercut his case against corporate social responsibility. In stating that managers shouldn’t use corporate resources at the expense of shareholders, even for purposes that a huge percentage of us would agree are good, Friedman argued that we should leave those functions to the government. He wrote:

On the level of political principle, the imposition of taxes and the expenditure of tax proceeds are governmental functions. We have established elaborate constitutional, parliamentary, and judicial provisions to assure that taxes are imposed so far as possible in accordance with the desires of the public—after all, “taxation without representation” was one of the battle cries of the American Revolution.

That ignores what we have learned, and Friedman learned, from the “Public Choice” school of economics, led by James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock. Government’s incentives are usually perverse and we see the bad results almost daily. There’s much more hope, and I think Friedman shared that hope, for private voluntary activity.

Read the whole thing.

(2 COMMENTS)

Source link

-

Business2 months ago

Business2 months agoBernice King, Ava DuVernay reflect on the legacy of John Lewis

-

World News2 months ago

Heavy rain threatens flood-weary Japan, Korean Peninsula

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoEverything New On Netflix This Weekend: July 25, 2020

-

Finance4 months ago

Will Equal Weighted Index Funds Outperform Their Benchmark Indexes?

-

Marketing Strategies9 months ago

Top 20 Workers’ Compensation Law Blogs & Websites To Follow in 2020

-

World News8 months ago

World News8 months agoThe West Blames the Wuhan Coronavirus on China’s Love of Eating Wild Animals. The Truth Is More Complex

-

Economy11 months ago

Newsletter: Jobs, Consumers and Wages

-

Finance10 months ago

Finance10 months ago$95 Grocery Budget + Weekly Menu Plan for 8