Economy

Will the mental scars of Covid fade or endure?

My local cheesemonger, having reinvented itself as a general produce store, has been open throughout lockdown. The proprietor tells me something strange and new has started to happen. Customers he hasn’t seen since March as they diligently shielded themselves from human contact, have finally re-emerged, blinking in the daylight. What’s more, he says, they have no concept of physical distance. While the rest of us have been honing our skills for 15 weeks, these poor souls haven’t got a clue how to behave when in public.

But then, do any of us, really? We’re all still working it out. Some people wonder around maskless, sneezing, snogging, shaking hands. Others are paranoid: “Keep two metres away from me! Get out into the road!”, I saw one masked gentleman scream as a perplexed woman jogged in his direction.

It’s a reminder that there is more to this pandemic than what governments tell us to do. Each of us has our own feelings about what is safe. Those emotions have shaped the arc of the pandemic. They will also define the path of the recovery.

Consider the impact of lockdowns. Common sense suggests they have been decisive in driving the disease into retreat, but they have not been the only factor. Hand-washing, handshake-aversion and working from home began long before legal enforcement.

A working paper from the economists Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson tries to separate out the effect of mandatory measures from voluntary ones in the US. For example, Illinois imposed restrictions before Wisconsin did. The researchers looked at activity on either side of such borders, using cell-phone data to track journeys to shops and other businesses. They were able to gain insight into how much of shutdown was effectively voluntary. The answer: a surprisingly large proportion. “Total foot traffic fell by more than 60 percentage points,” they write. “Legal restrictions explain only around 7 percentage points of that.” The shutdown, then, was roughly 10 per cent mandatory; it was 90 per cent voluntary.

A similar message comes from a comparison of Denmark, which had a firm lockdown, with Sweden, with its notoriously light-touch approach. Aggregate spending dropped 29 per cent in Denmark and 25 per cent in Sweden. That means voluntary measures did much of the damage to the economy — and, one hopes, have delivered much of the public-health benefit too.

I wouldn’t put too much weight on the precise numbers, but the basic message is important. People didn’t lock down merely because governments told them to. Now the converse applies: just because shopping is legal again does not mean people will rush out to the shops.

In Germany, they did: Germans spent more in May 2020 than they did in May 2019, suggesting that not only were they willing to visit the shops, they wanted to make up for lost time.

That is encouraging, but only up to a point. Germany had a good crisis by western standards, with fewer than 10,000 excess deaths, compared with 25,000 in France, nearly 50,000 in Italy and Spain, and more than 65,000 in the UK. The US is currently averaging about a hundred times as many daily new cases as Germany. Perhaps Germans feel safe because they are safe. Not everyone can say that.

Once the virus is suppressed, then a sharp recovery is possible. But might this experience leave a lasting mark on our thinking? Perhaps so. The economist Ulrike Malmendier has published several studies suggesting that our early economic experiences can be formative of enduring attitudes. If the stock market is weak when we are young adults, we tend to shy away from investing, permanently. Similarly, the hawkishness or dovishness of Federal Open Market Committee members is shaped by their personal experience of inflation.

A new working paper by Prof Malmendier and Leslie Sheng Shen suggests recessions reshape consumer behaviour long after they have passed. The after-effects are wonderfully described as “experience-induced frugality” — that is, people who’ve seen periods of high unemployment save more and accumulate wealth, just in case.

Such thrift could lead to more investment, of course, but another recent paper by Julian Kozlowski, Laura Veldkamp, and Venky Venkateswaran argues otherwise. They assert that the psychological scarring is destructive, since a vivid appreciation of catastrophic scenarios will leave people fearful of making bold investments. Why risk anything in a capricious universe?

I wonder. We do learn from bitter experience, of course. But we also have a great talent for forgetting. In particular, we forget how bad things feel. The pandemic will long be remembered, but the pain will fade. After Hurricane Katrina, the US National Flood Insurance Program saw a spike in demand. Three years on, demand for flood insurance had fallen back to pre-Katrina levels.

My guess is that clever statisticians will be able to detect the psychological aftershocks of the pandemic for decades to come — but that, to a casual gaze, everyday life in 2022 will look a lot like it did in 2018. Scars do not always heal, but they fade.

Written for and first published in the Financial Times on 03 July 2020.

My new book The Next Fifty Things That Made the Modern Economy is NOW OUT. Details, and to order on Hive, Blackwells, Amazon or Watersones. Bill Bryson comments, “Endlessly insightful and full of surprises — exactly what you would expect from Tim Harford.”

Economy

Dorothy Theresa Sawchak Mankiw

Above is a picture of my mother as a young woman. I would like to tell you about her.

My mother was born on July 18, 2020, the second child of Nicholas and Catherine Sawchak.

Nicholas and Catherine were immigrants from Ukraine. They came to the United States as teenagers, arriving separately, neither with more than a fourth-grade education. Catherine was from a farming area in western Ukraine. She left because her family wanted her to marry an older man rather than her younger boyfriend, who had been conscripted into the army. Her first job here was as a maid. Nicholas was from Kiev, where he had been trained to be a furrier. In the United States, he worked as a potter, making sinks and toilettes. When Nicholas and Catherine came to the United States, they thought they might return home to Ukraine eventually. But World War I and the Russian Revolution intervened, causing a change of plans. Catherine’s boyfriend died in the war. Nicholas and Catherine met each other, married, and settled in a small row house in Trenton, New Jersey, where they lived the rest of their lives.

Catherine and Nicholas had two children, my uncle Walter and my mother Dorothy. When my mother was born, her parents chose to name her “Dorothy Theresa Sawchak.” But because Catherine spoke with a heavy accent, the clerk preparing the birth certificate did not understand her. So officially, my mother’s middle name was “Tessie” rather than “Theresa.” She never bothered to change it.

Nicholas and Catherine were hardworking and frugal. They saved enough to send Walter to college and medical school. He served as a physician in the army during the Korean war. Once I asked him if he worked at a MASH unit, like in the TV show. He said no, he worked closer to the front. He patched up the wounded soldiers the best he could and then sent them to a MASH unit to recover and receive more treatment. After the war, he became a pathologist in a Trenton-area hospital. He married and had two daughters, my cousins.

My mother attended Trenton High School (the same high school, I learned years later, attended by the economist Robert Solow at about the same time). She danced ballet. She water-skied on the Delaware River. She loved to read and go to the movies.

In part because of limited resources and in part because of the gender bias of the time, my mother was not given the chance to go to college. Years later, her parents would say that not giving her that opportunity was one of their great regrets. Instead, my mother learned to be a hairdresser. She was also pressured to marry the son of some family friends.

The marriage did not work. With my mother pregnant, her new husband started “running around,” my mother’s euphemism for infidelity. They divorced, and she kicked him out of her life. But the marriage did leave her with one blessing—my sister Peg.

My mother continued life as a single mother. Some years later, she met my father, also named Nicholas, through social functions run by local Ukrainian churches. They both loved to dance. He wanted to marry her, but having been burned once, she was reluctant at first. Only when she realized that he had become her best friend did she finally accept.

In 1958, nine months after I was born, Mom, Dad, Peg, and I left Trenton for a newly built split-level house in Cranford, New Jersey. My father was working for Western Electric, an arm of AT&T, first as a draftsman and then as an electrical engineer. He worked there until his retirement. One of his specialties was battery design. When I was growing up, I thought it sounded incredibly boring. Now I realize how important it is.

My mother then stopped working as a hairdresser to become a full-time mom. But she kept all the hairdresser equipment from her shop—chair, mirrors, scissors, razors, and so on—in our basement. She would cut the hair of her friends on a part-time basis. When I was a small boy, she cut my hair as well.

I attended the Brookside School, the public grade school which was a short walk from our house. When I was in the second or third grade, my mother was called in to see the teacher. The class had been given some standardized aptitude test. “Greg did well,” the teacher said. “We were very surprised.”

At that moment, my mother decided the school was not working out for me. I was talkative and inquisitive at home but shy and lackluster at school. I needed a change.

She started looking around for the best school she could find for me. She decided it was The Pingry School, an independent day school about a dozen miles from our house. She had me apply, and I was accepted.

The question then became, how to pay for it? Pingry was expensive, and we did not have a lot of extra money. My mother decided that she needed to return to work.

She started looking for a job, and an extraordinary opportunity presented itself. Union County, where we lived, was opening a public vocational school, and they were looking for teachers. She applied to be the cosmetology teacher and was hired.

There was, however, a glitch. The teachers, even though teaching trades like hairdressing, needed teacher certification. That required a certain number of college courses, and my mother had not taken any. So she got a temporary reprieve from the requirement. While teaching at the vocational school during the day, she started taking college courses at night to earn her certification, all while raising two children.

My mother taught at the vocational school until her retirement. During that time, she also co-authored a couple of books, called Beauty Culture I and II, which were teacher’s guides. From the summary of the first volume: “The syllabus is divided into six sections and includes the following areas of instruction: shop, school, and the cosmetologist; sterilization practices in the beauty salon; scalp and hair applications and shampooing; hair styling; manicuring; and hairpressing and iron curling.” I suppose one might view this project as a harbinger of my career as a textbook author.

When my parents both retired, they were still the best of friends. They traveled together, exploring the world in ways that were impossible when they were younger and poorer. During my third year as an economics professor, I was visiting the LSE for about a month. I encouraged my parents to come over to London for a week or so. They had a grand time. I believe it was the first time they had ever visited Europe. When I was growing up, vacations were usually at the Jersey shore.

My father died a few years later. My mother spent the next three decades living alone. She was then living full-time at the Jersey shore in Brant Beach on Long Beach Island. The house was close to the ocean and large enough to encourage her growing family to come for extended visits. Two children, five grandchildren, four great-grandchildren. The more, the merrier. Nothing made her happier than being surrounded by family.

My mother loved to cook, especially the Ukrainian dishes she learned in her childhood. Holubtsi (stuffed cabbage) was a specialty. Another was kapusta (cabbage) soup. One time, the local newspaper offered to publish her kapusta soup recipe. They did so, but with an error. Every seasoning that was supposed to be measured in teaspoons was printed as tablespoons. The paper later ran a correction but probably to no avail. I am not sure if anyone ever tried the misprinted recipe and, if so, to what end.

During her free time in her later years, my mother read extensively, played FreeCell on her computer, and watched TV. A few years ago, when she was about 90 years old, I was visiting her, and I happened to mention the show “Breaking Bad.” She had not heard of it. She suggested we watch the first episode. And then another. And another. After I left, she binge-watched all five seasons.

As she aged, living alone became harder. When she had trouble going up and down the stairs, an elevator was added to her house. But slowly her balance faltered, and she fell several times. She started having small strokes, and then a more significant one. She moved into a nursing home. Whenever I visited, I brought her new books to read. Her love of reading never diminished.

This is, I am afraid, where the story ends. Last week, Dorothy Theresa Sawchak Mankiw tested positive for Covid-19. Yesterday, she died. I will miss her.

Source link

Economy

The GDP Collapse: It Is What It Is

Jim discussed elements of the 2020Q2 advance release on Thursday. Here, I amplify some aspects that he mentioned.

Confirmation: A Catastrophe in the Making

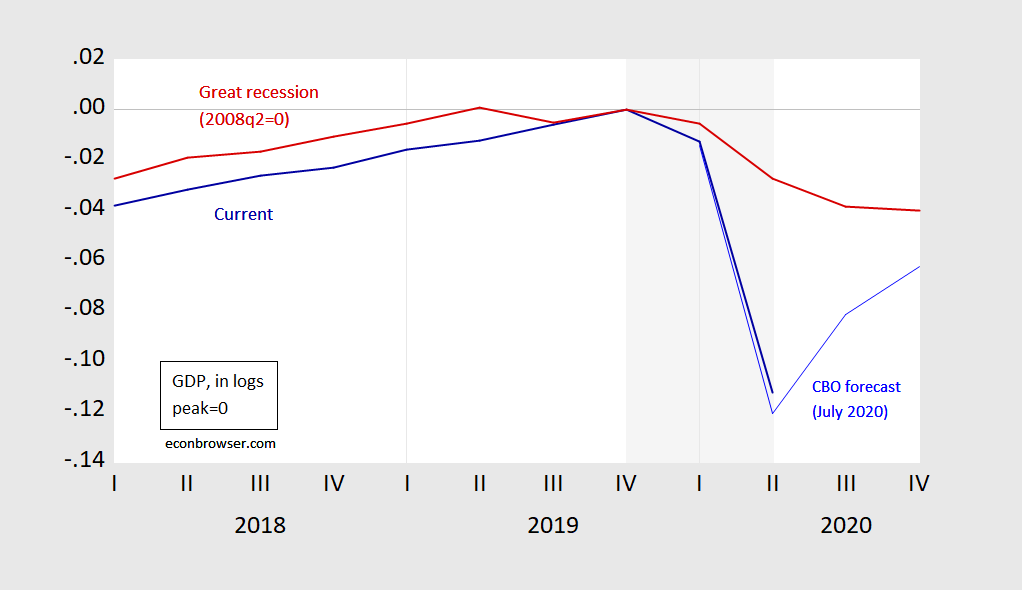

First, the Trump recession is truly catastrophic in scale; the pace of GDP decline is much greater than that in 2008. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: GDP in logs, normalized to 0 at 2019Q4 (NBER peak) (blue), and GDP normalized to 2008Q2 (red). NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming trough at 2020Q2. Source: BEA, 2020Q2 advance release, CBO An Update to the Economic Outlook (July), NBER, author’s calculations.

A “No Confidence” Vote in Administration Policy and Investment

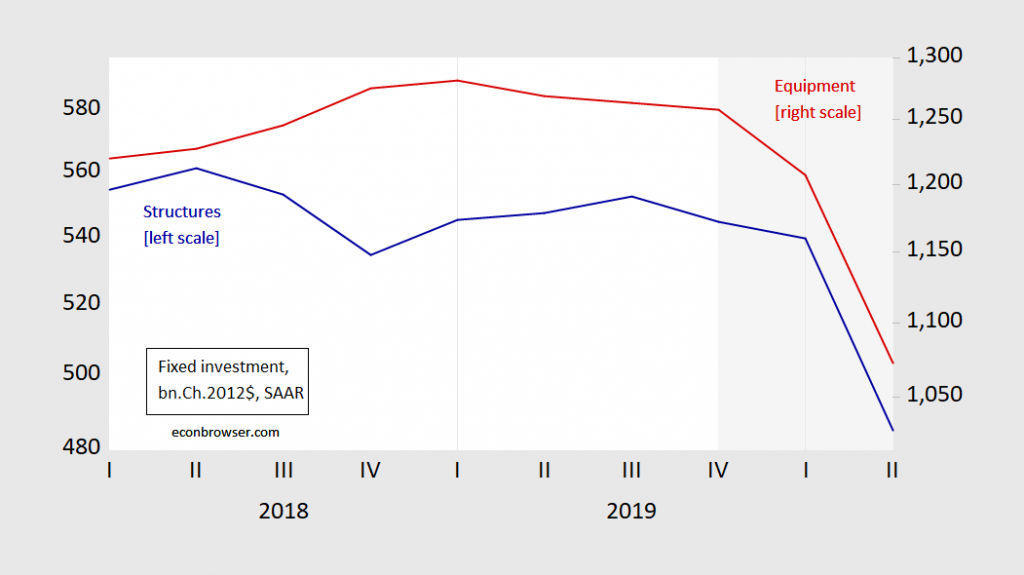

Second, investment has crashed — for both structures and equipment investment. That’significant insofar as capital investment is forward looking.

Figure 2: Fixed investment in structures (blue, left log scale), and in equipment (red, right log scale), in billions Chained 2012$, SAAR. NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming trough at 2020Q2. Source: BEA, 2020Q2 advance release, NBER, author’s calculations.

This decline is even more rapid than in 2008Q4; 31.5% now vs. 24% then.

Figure 3: Nonresidential fixed investment in logs, normalized to 0 in 2019Q4 (blue), and normalized to 0 in 2008Q2 (red). NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming trough at 2020Q2. Source: BEA, 2020Q2 advance release, NBER, author’s calculations.

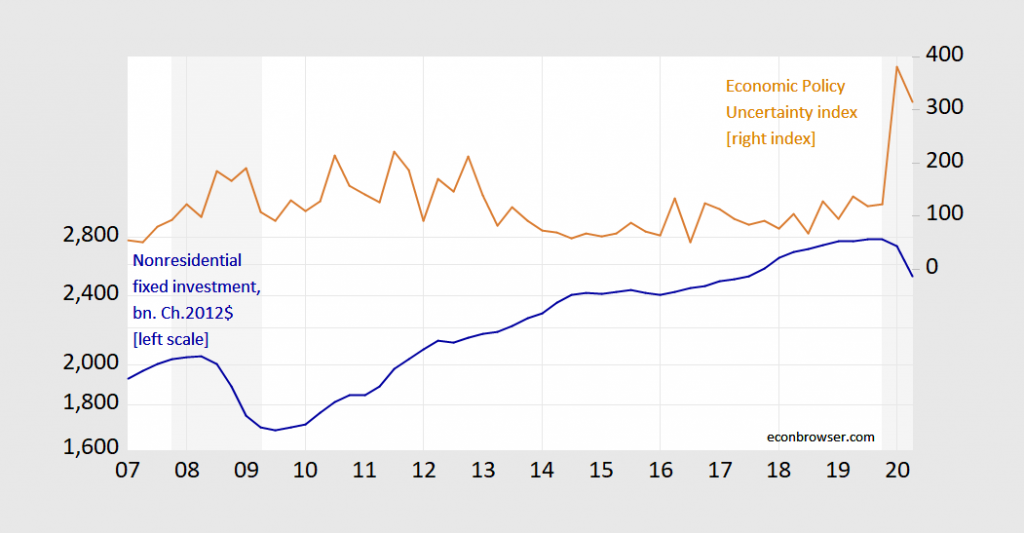

Certainly, some of the crash is due to the crash in aggregate demand — as in the 2007 recession — but some is due to uncertainty, including policy uncertainty. Policy uncertainty levels currently dwarf those of the Great Recession.

Figure 4: Nonresidential fixed investment in billions Chained 2012$ SAAR (blue, left log scale), Economic Policy Uncertainty index (tan, right scale). NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming trough at 2020Q2. Source: BEA, 2020Q2 advance release, NBER, policyuncertainty.com via FRED, and author’s calculations.

No Recovery Without Recovery in Services Demand

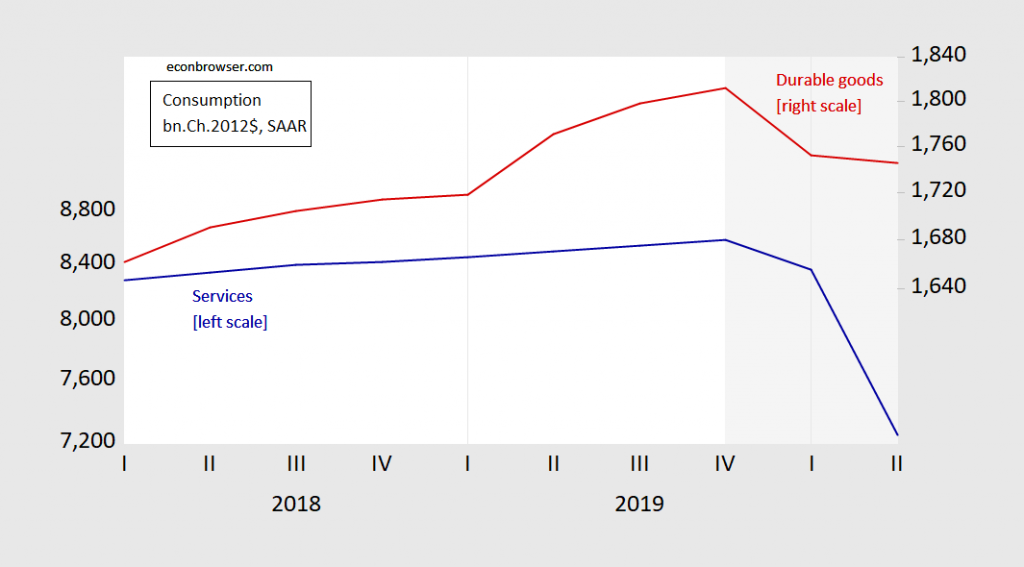

Third, this is a different kind of recession, in many ways, but importantly in the sectoral origin. As Jim Hamilton noted, the decline in services consumption was 43.5% on an annualized basis, while durable goods consumption was relatively flat.

Figure 5: Services consumption (blue, left log scale), and durable goods consumption (red, right log scale), all in billions Chained 2012$ SAAR. NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming trough at 2020Q2. Source: BEA, 2020Q2 advance release, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Of the 9.8 percentage point decline in GDP (not annualized), 5.9 percentage points were accounted for (in a mechanical sense) by services consumption decline. Jim provides a breakdown of the services consumption decline in his post.

Services consumption will not fully recover until such time as the Covid-19 infection rates are at manageable levels that do not deter such consumption activities. The Administration’s current policy stance is unlikely to encourage that development; one could argue that it — in toto — is impeding that outcome.

State and Local Government Spending Collapses

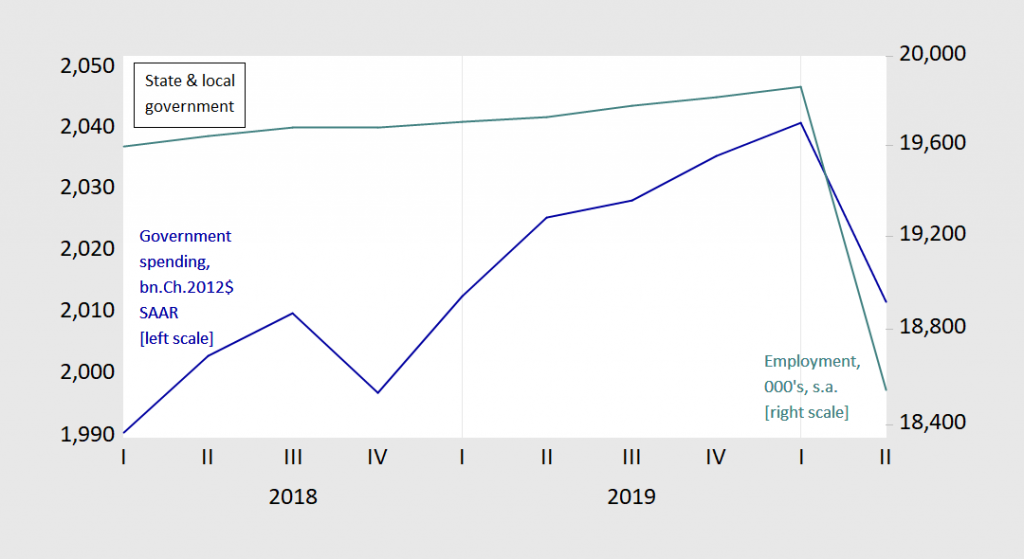

Fourth, the biggest threat to the economy may be avoidable. One of the lessons of the Great Recession is that constraints on state and local government spending — exacerbated by ill-advised state income tax cuts — was one of the reasons for the torpid pace of recovery. So far, we have not replicated completely that experience, but with Republican opposition to further Federal transfers to the state, we are in danger of repeating that error.

Figure 6: State and local government spending, billions Chained 2012$ SAAR (blue, left log scale), and state and local employment, 000’s, s.a. (teal, right log scale). Source: BEA 2020Q2 advance release, BLS employment situation June release.

This is why it is critical, as many economists have argued, for the next recovery package to include substantial aid to the states and localities.

Economy

Bonus Quotation of the Day…

… is from pages 314-315 of George Will’s great 2019 book, The Conservative Sensibility:

America’s poverty problem is not one of material scarcities but of abundant bad behavior. Data demonstrate that there are three simple behavioral rules for avoiding poverty: finish high school, produce no child before marrying or before age twenty. Only 8 percent of families who conform to all three rules are poor; 79 percent of those who do not conform are poor. And recent social learning includes this: The trajectory of a child’s life is largely determined in the early years.

DBx: I don’t wish to come across as self-flattering, but as I’ve written before, I cannot help but draw some lessons from my own personal experience. I was born in 1958 into a thoroughly working-class American family. My mother, Carolyn, graduated from high-school. (I, the oldest of her four children, was born when she was 20.) My father, Buddy, dropped out of school in 6th grade. When I was born he, at the age of 23, was driving a bus for New Orleans Public Service (“NOPSI” as it was called). He soon afterward got a job as a pipe fitter at Avondale Shipyards, where he worked until he retired in January 2001. On more than one occasion dad was laid off from his job before being called back.

While growing up I didn’t think of us as being poor, although I was well aware that we were far from rich. And when my parents died - mom in March 2008 and dad in April 2009 - sure enough the monetary inheritance was meager.

But my family was loving and stable. Dad was always with his family when he wasn’t at work. He and mom drank very little and took no illicit drugs. My siblings and I were disciplined in the manner of the day - which means that sometimes we got physically spanked. Yet there was never a doubt in my mind - or in the minds of any of my three siblings - that we were loved.

Most importantly, my parents instilled in us a deep belief that the world owes us nothing and that we are responsible for our lives. Excuses for bad grades or bad behavior were simply not tolerated. Ever. There was, further, no tolerance for feeling sorry for ourselves. The notion of envying other people - and we encountered many - who were materially more prosperous than us was out of the question.

My parents were loving, not harsh. They were judgmental only about deviance from acting in accordance with basic life skills and fundamental values - skills and values such as being polite, being punctual, being honest, never being boastful, working hard, and, again, avoiding envy and self-pity as if these sentiments are genuinely dangerous plagues (which these sentiments in fact are).

All four of my parents’ children today lead productive lives. None is poor by American standards. Each has raised their own productive and responsible children.

Among the absolute worst curses that can afflict a person is to grow up slathered with the belief that the world owes something positive to him or her, and not be firmly discouraged from blaming one’s current condition in life on others or on the fates.

The post Bonus Quotation of the Day… appeared first on Cafe Hayek.

-

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoBernice King, Ava DuVernay reflect on the legacy of John Lewis

-

World News3 weeks ago

Heavy rain threatens flood-weary Japan, Korean Peninsula

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoEverything New On Netflix This Weekend: July 25, 2020

-

Finance3 months ago

Will Equal Weighted Index Funds Outperform Their Benchmark Indexes?

-

Marketing Strategies7 months ago

Top 20 Workers’ Compensation Law Blogs & Websites To Follow in 2020

-

World News7 months ago

World News7 months agoThe West Blames the Wuhan Coronavirus on China’s Love of Eating Wild Animals. The Truth Is More Complex

-

Economy9 months ago

Newsletter: Jobs, Consumers and Wages

-

Finance8 months ago

Finance8 months ago$95 Grocery Budget + Weekly Menu Plan for 8