Economy

The Surplus Process

How should we model surpluses and deficits? In finishing up a recent articleand chapter 5 and 6 of a Fiscal Theory of the Price Level update, a bunch of observations coalesced that are worth passing on in blog post form.

Background: The real value of nominal government debt equals the present value of real primary surpluses, [ frac{B_{t-1}}{P_{t}}=b_{t}=E_{t}sum_{j=0}^{infty}beta^{j}s_{t+j}. ] I ‘m going to use one-period nominal debt and a constant discount rate for simplicity. In the fiscal theory of the price level, the (B) and (s) decisions cause inflation (P). In other theories, the Fed is in charge of (P), and (s) adjusts passively. This distinction does not matter for this discussion. This equation and all the issues in this blog post hold in both fiscal and standard theories.

The question is, what is a reasonable time-series process for (left{s_{t}right} ) consistent with the debt valuation formula? Here are surpluses

The blue line is the NIPA surplus/GDP ratio. The red line is my preferred measure of primary surplus/GDP, and the green line is the NIPA primary surplus/GDP.

The surplus process is persistent and strongly procyclical, strongly correlated with the unemployment rate. (The picture is debt to GDP and surplus to GDP ratios, but the same present value identity holds with small modifications so for a blog post I won’t add extra notation.)

Something like an AR(1) quickly springs to mind, [ s_{t+1}=rho_{s}s_{t}+varepsilon_{t+1}. ] The main point of this blog post is that this is a terrible, though common, specification.

Write a general MA process, [ s_{t}=a(L)varepsilon_{t}. ] The question is, what’s a reasonable (a(L)?) To that end, look at the innovation version of the present value equation, [ frac{B_{t-1}}{P_{t-1}}Delta E_{t}left( frac{P_{t-1}}{P_{t}}right) =Delta E_{t}sum_{j=0}^{infty}beta^{j}s_{t+j}=sum_{j=0}^{infty}beta ^{j}a_{j}varepsilon_{t}=a(beta)varepsilon_{t}% ] where [ Delta E_{t}=E_{t}-E_{t-1}. ] The weighted some of moving average coefficients (a(beta)) controls the relationship between unexpected inflation and surplus shocks. If (a(beta)) is large, then small surplus shocks correspond to a lot of inflation and vice versa. For the AR(1), (a(beta)=1/(1-rho_{s}beta)approx 2.) Unexpected inflation is twice as volatile as unexpected surplus/deficits.

(a(beta)) captures how much of a deficit is repaid. Consider (a(beta)=0). Since (a_{0}=1), this means that the moving average is s-shaped. For any (a(beta)lt 1), the moving average coefficients must eventually change sign. (a(beta)=0) is the case that all debts are repaid. If (varepsilon_{t}=-1), then eventually surpluses rise to pay off the initial debt, and there is no change to the discounted sum of surpluses. Your debt obeys (a(beta)=0) if you do not default. If you borrow money to buy a house, you have deficits today, but then a string of positive surpluses which pay off the debt with interest.

The MA(1) is a good simple example, [ s_{t}=varepsilon_{t}+thetavarepsilon_{t-1}% ] Here (a(beta)=1+thetabeta). For (a(beta)=0), you need (theta=-beta ^{-1}=-R). The debt -(varepsilon_{t}) is repaid with interest (R).

Let’s look at an estimate. I ran a VAR of surplus and value of debt (v), and I also ran an AR(1).

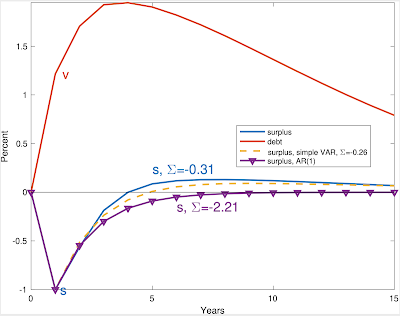

Here are the response functions to a deficit shock:

The blue solid line with (s=-0.31) comes from a larger VAR, not shown here. The dashed line comes from the two variable VAR, and the line with triangles comes from the AR(1).

The VAR (dashed line) shows a slight s shape. The moving average coefficients gently turn positive. But when you add it up, those overshootings bring us back to (a(beta)=0.26) despite 5 years of negative responses. (I use (beta=1)). The AR(1) version without debt has (a(beta)=2.21), a factor of 10 larger!

Clearly, whether you include debt in a VAR and find a slightly overshooting moving average, or leave debt out of the VAR and find something like an AR(1) makes a major difference. Which is right? Just as obviously, looking at (R^2) and t-statistics of the one-step ahead regressions is not going to sort this out.

I now get to the point.

Here are 7 related observations that I think collectively push us to the view that (a(beta)) should be a quite small number. The observations use this very simple model with one period debt and a constant discount rate, but the size and magnitude of the puzzles are so strong that even I don’t think time-varying discount rates can overturn them. If so, well, all the more power to the time-varying discount rate! Again, these observations hold equally for active or passive fiscal policy. This is not about FTPL, at least directly.

1) The correlation of deficits and inflation. Reminder, [ frac{B_{t-1}}{P_{t-1}}Delta E_{t}left( frac{P_{t-1}}{P_{t}}right) =a(beta)varepsilon_{t}. ] If we have an AR(1), (a(beta)=1/(1-rho_{s}beta)approx2), and with (sigma(varepsilon)approx5%) in my little VAR, the AR(1) produces 10% inflation in response to a 1 standard deviation deficit shock. We should see 10% unanticipated inflation in recessions! We see if anything slightly less inflation in recessions, and little correlation of inflation with deficits overall. (a(beta)) near zero solves that puzzle.

2) Inflation volatility. The AR(1) likewise predicts that unexpected inflation has about 10% volatility. Unexpected inflation has about 1% volatility. This observation on its own suggests (a(beta)) no larger than 0.2.

3) Bond return volatility and cyclical correlation. The one-year treasury bill is (so far) completely safe in nominal terms. Thus the volatility and cyclical correlation of unexpected inflation is also the volatility and cyclical correlation of real treasury bill returns. The AR(1) predicts that one-year bonds have a standard deviation of returns around 10%, and they lose in recessions, when the AR(1) predicts a big inflation. In fact one-year treasury bills have no more than 1% standard deviation, and do better in recessions.

4) Mean bond returns. In the AR(1) model, bonds have a stock-like volatility and move procyclically. They should have a stock-like mean return and risk premium. In fact, bonds have low volatility and have if anything a negative cyclical beta so yield if anything less than the risk free rate. A small (a(beta)) generates low bond mean returns as well.

Jiang, Lustig, Van Nieuwerburgh and Xiaolan recently raised this puzzle, using a VAR estimate of the surplus process that generates a high (a(beta)). Looking at the valuation formula [ frac{B_{t-1}}{P_{t}}=E_{t}sum_{j=0}^{infty}beta^{j}s_{t+j}, ] since surpluses are procyclical, volatile, and serially correlated like dividends, shouldn’t surpluses generate a stock-like mean return? But surpluses are crucially different from dividends because debt is not equity. A low surplus (s_{t}) raises our estimate of subsequent surpluses (s_{t+j}). If we separate out

[b_{t}=s_{t}+E_{t}sum_{j=1}^{infty}beta^{j}s_{t+j}=s_{t}+beta E_{t}b_{t+1} ] a decline in the “cashflow” (s_{t}) raises the “price” term (b_{t+1}), so the overall return is risk free. Bad cashflow news lowers stock pries, so both cashflow and price terms move in the same direction. In sum a small (a(beta)lt 1) resolves the Jiang et. al. puzzle. (Disclosure, I wrote them about this months ago, so this view is not a surprise. They disagree.)

5) Surpluses and debt. Looking at that last equation, with a positively correlated surplus process (a(beta)>1), as in the AR(1), a surplus today leads to larger value of the debt tomorrow. A deficit today leads to lower value of the debt tomorrow. The data scream the opposite pattern. Higher deficits raise the value of debt, higher surpluses pay down that debt. Cumby_Canzoneri_Diba (AER 2001) pointed this out 20 years ago and how it indicates an s-shaped surplus process. An (a(beta)lt 1) solves their puzzle as well. (They viewed (a(beta)lt 1) as inconsistent with fiscal theory which is not the case.)

6) Financing deficits. With (a(beta)geq1), the government finances all of each deficit by inflating away outstanding debt, and more. With (a(beta)=0), the government finances deficits by selling debt. This statement just adds up what’s missing from the last one. If a deficit leads to lower value of the subsequent debt, how did the government finance the deficit? It has to be by inflating away outstanding debt. To see this, look again at inflation, which I write [ frac{B_{t-1}}{P_{t-1}}Delta E_{t}left( frac{P_{t-1}}{P_{t}}right) =Delta E_{t}s_{t}+Delta E_{t}sum_{j=1}^{infty}beta^{j}s_{t+j}=Delta E_{t}s_{t}+Delta E_{t}beta b_{t+1}=1+left[ a(beta)-1right] varepsilon_{t}. ] If (Delta E_{t}s_{t}=varepsilon_{t}) is negative — a deficit — where does that come from? With (a(beta)>1), the second term is also negative. So the deficit, and more, comes from a big inflation on the left hand side, inflating away outstanding debt. If (a(beta)=0), there is no inflation, and the second term on the right side is positive — the deficit is financed by selling additional debt. The data scream this pattern as well.

7) And, perhaps most of all, when the government sells debt, it raises revenue by so doing. How is that possible? Only if investors think that higher surpluses will eventually pay off that debt. Investors think the surplus process is s-shaped.

All of these phenomena are tied together. You can’t fix one without the others. If you want to fix the mean government bond return by, say, alluding to a liquidity premium for government bonds, you still have a model that predicts tremendously volatile and procyclical bond returns, volatile and countercyclical inflation, deficits financed by inflating away debt, and deficits that lead to lower values of subsequent debt.

So, I think the VAR gives the right sort of estimate. You can quibble with any estimate, but the overall view of the world required for any estimate that produces a large (a(beta)) seems so thoroughly counterfactual it’s beyond rescue. The US has persuaded investors, so far, that when it issues debt it will mostly repay that debt and not inflate it all away.

Yes, a moving average that overshoots is a little unusual. But that’s what we should expect from debt. Borrow today, pay back tomorrow. Finding the opposite, something like the AR(1), would be truly amazing. And in retrospect, amazing that so many papers (including my own) write this down. Well, clarity only comes in hindsight after a lot of hard work and puzzles.

In more general settings (a(beta)) above zero gives a little bit of inflation from fiscal shocks, but there are also time-varying discount rates and long term debt in the present value formula. I leave all that to the book and papers.

(Jiang et al say they tried it with debt in the VAR and claim it doesn’t make much difference. But their response functions with debt in the VAR, at left, show even more overshooting than in my example, so I don’t see how they avoid all the predictions of a small (a(beta)), including a low bond premium.)

A lot of literature on fiscal theory and fiscal sustainability, including my own past papers, used AR(1) or similar surplus processes that don’t allow (a(beta)) near zero. I think a lot of the puzzles that literature encountered comes out of this auxiliary specification. Nothing in fiscal theory prohibits a surplus process with (a(beta)=0) and certainly not (0 lt a(beta)lt 1).

Update

Jiang et al. also claim that it is impossible for any government with a unit root in GDP to issue risk free debt. The hidden assumption is easy to root out. Consider the permanent income model, [ c_t = rk_t + r beta sum beta^j y_{t+j}] Consumption is cointegrated with income and the value of debt. Similarly, we would normally write the surplus process [ s_t = alpha b_t + gamma y_t. ] responding to both debt and GDP. If surplus is only cointegrated with GDP, one imposes ( alpha = 0), which amounts to assuming that governments do not repay debts. The surplus should be cointegrated with GDP and with the value of debt. Governments with unit roots in GDP can indeed promise to repay their debts.

Source link

Economy

UI claims and GDP growth are historically bad: Now is not the time to cut benefits that are supporting jobs

Last week 2 million workers applied for unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. Breaking that down: 1.2 million applied for regular state unemployment insurance (not seasonally adjusted), and 830,000 applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). Many headlines this morning are saying there were 1.4 million UI claims last week, but that’s not the right number to use. For one, it ignores PUA, the federal program that is serving millions of workers who are not eligible for regular UI, like the self-employed. It also uses seasonally adjusted data, which is distorted right now because of the way Department of Labor (DOL) does seasonal adjustments.

Last week was the 19th week in a row that unemployment claims have been more than twice the worst week of the Great Recession. If you restrict this comparison just to regular state claims—because we didn’t have PUA in the Great Recession—this is the 19th week in a row that claims are more than 1.25 times the worst week of the Great Recession.

Republicans in the Senate just allowed the across-the-board $600 increase in weekly UI benefits to expire. They are proposing to (essentially) replace it with a $200 weekly payment. That $400 cut in benefits is not just cruel, it’s terrible economics. These benefits are supporting a huge amount of spending by people who would otherwise have to cut back dramatically. The spending made possible by the $400 that the Senate wants to cut is supporting 3.4 million jobs. If you cut the $400, you cut those jobs. This map shows the number of jobs that will be lost in each state if the extra $600 unemployment benefit is cut to $200.

Today’s release of GDP data underscores how wrong it is to cut those benefits. Second-quarter GDP collapsed at the fastest rate on record—and the second quarter includes the employment bounce-back of May and June. And because we did not put the public health measure in place necessary to successfully reopen, the coronavirus has spiked, and the economic improvement we saw in May and June has stalled, if not reversed. Now is not the time to cut benefits that are supporting jobs.

But what about the potential work disincentive of the extra $600? After all, the additional payment means many people have higher income on unemployment insurance than they did from their prior job. It turns out that the concern about the disincentive effect has been massively overblown. In fact, rigorous empirical studies show that any theoretical disincentive effect has been so minor that it cannot even be detected. For example, a new study by Yale economists found no evidence that recipients of more generous benefits were less likely to return to work. A case in point: in May and June—with the $600 in place—7.5 million people went back to work. And, about 70% of likely UI recipients who returned to work were making more on UI than their prior wage. Further, there are 14 million more unemployed workers than job openings, meaning millions will remain jobless no matter what they do. Slashing the $600 cannot incentivize people to get jobs that are not there. Even further, many people are simply unable to take a job right now because it’s not safe for them or their family, or because they have care responsibilities as a result of the virus. Slashing the $600 cannot incentivize them to get jobs, it will just cause hardship.

Slashing the $600 will also exacerbate racial inequality. Due to the impact of historic and current systemic racism, Black and brown communities are suffering more from this pandemic, and have less wealth to fall back on. They will take a much bigger hit if the $600 is cut. This is particularly true for Black and brown women and their families, because in this recession, these women have seen the largest job losses of all.

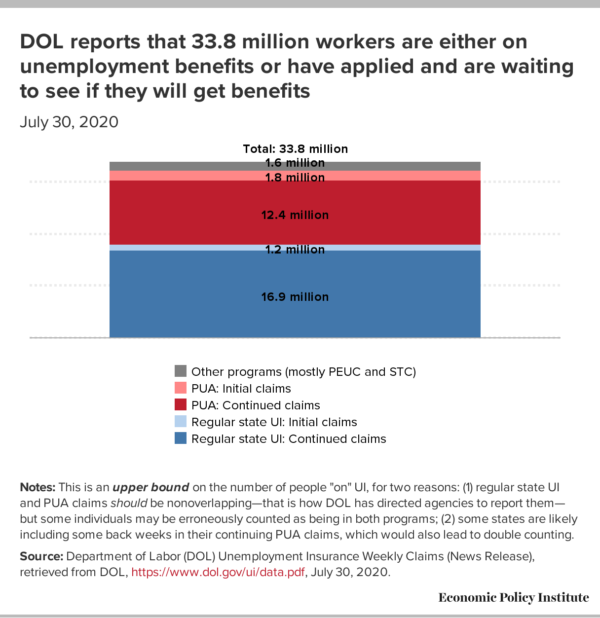

Figure B combines the most recent data on both continuing claims and initial claims to get a measure of the total number of people “on” unemployment benefits as of July 25. DOL numbers indicate that right now, 33.8 million workers are either on unemployment benefits, have been approved and are waiting for benefits, or have applied recently and are waiting to get approved. But importantly, Figure B provides an upper bound on the number of people “on” UI, for two reasons: (1) Some individuals may be being counted twice. Regular state UI and PUA claims should be non-overlapping—that is how DOL has directed state agencies to report them— but some individuals may be erroneously counted as being in both programs; (2) Some states are likely including some back weeks in their continuing PUA claims, which would also lead to double counting (the discussion around Figure 3 in this paper covers this issue well).

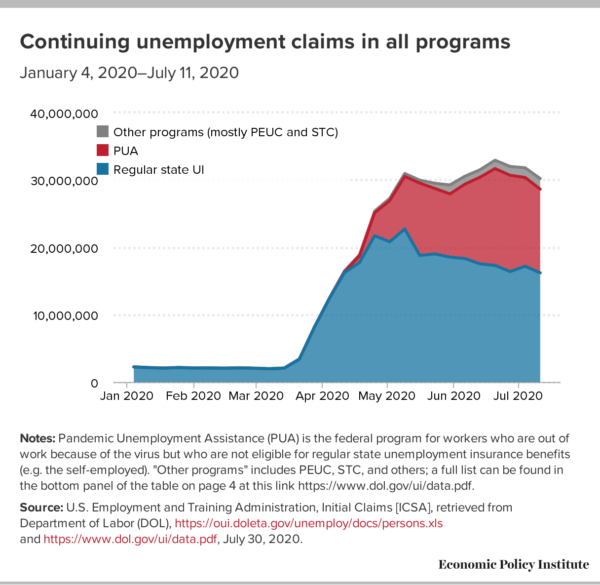

Figure C shows continuing claims in all programs over time (the latest data are for July 11). Continuing claims are more than 28 million above where they were a year ago. However, the above caveat about potential double counting applies here too, which means the trends over time should be interpreted with caution.

Economy

Silence is Stupid, Argument is Foolish

When I was young, I never backed down in an intellectual argument. Part of the reason, admittedly, was that I was starved for abstract debate. Before the internet, anyone who wanted to talk ideas had to corner an actual human willing to do the same. Another big reason, though, was that I didn’t want to look stupid. A smart person always has a brilliant riposte, right? And if you shut up, it must be because you’re stumped.

At this stage in my life, much has changed. Public debates aside, I now only engage in intellectual arguments with thinkers who play by the rules. What rules? For starters: remain calm, take nothing personally, use probabilities, face hypotheticals head-on, and spurn Social Desirability Bias like the plague. If I hear someone talking about ideas who ignores these rules, I take evasive action. If cornered, I change the subject.

Why? Because I now realize that arguing with unreasonable people is foolish. Young people might learn something at the meta-level - such as “Wow, so many people are so unreasonable.” But I’m long past such doleful lessons. Note: “Being unreasonable” is not a close synonym for “Agrees with me.” Most people who agree with me are still aggressively unreasonable. Instead, being reasonable is about sound intellectual methods - remaining calm, taking nothing personally, using probabilities, facing hypotheticals head-on, spurning Social Desirability Bias, and so on.

In classic Dungeons & Dragons, characters have two mental traits: Intelligence and Wisdom. The meaning matches everyday English: high-Intelligence characters are good at solving complex puzzles; high-Wisdom characters have a generous helping of common-sense.

Using the game to illuminate life: Running out of things in say in an argument is indeed a sign of low Intelligence, just as I held when I was a teenager. A genius never runs out of rebuttals. At the same time, however, joining a fruitless dispute is a sign of low Wisdom. You have better things to do with your life than tell hyperventilating people all the reasons they’re wrong. A really wise person won’t merely break off such exchanges, but stop them before they start - and get back to work on his Bubble.

Here, in short, is wisdom: Be not a hostage to your own intellectual pride.

P.S. How do you know if a person plays by the rules until you actually engage them? Most obviously, watch how they argue with other people! If that’s inadequate, give promising strangers a brief trial period, but be ready to disengage if things go south.

(1 COMMENTS)

Source link

Economy

On the Impossibility of Intellectual Property

Abstract: The concept of intellectual property (IP) has been variously criticized as incompatible with natural rights and detrimental to the dissemination of innovations. In this paper I argue that it can be criticized on an even more fundamental level—namely as a praxeological impossibility. More specifically, it is suggested that since ideas are not economic goods, but preconditions of action, and since physical goods transformed by ideas become as heterogeneous (and thus as intellectually unique) as the individuals who enact such transformations, no economic goods can be meaningfully designated as appropriable in virtue of embodying the objectively definable value of one’s intellectual labor. In view of the above, I subsequently suggest that IP protection laws constitute an exceptionally arbitrary and thus exceptionally disruptive form of interventionism directed against the very essence of the entrepreneurial market process.

JEL Classification: K00, L26, O34, P48

Jakub Bożydar Wiśniewski ([email protected]) is an assistant professor at the Institute of Economics at the University of Wroclaw and an affiliated scholar with the Ludwig von Mises Institute Poland.

1. INTRODUCTION

The concept of intellectual property (IP) has been criticized from a number of distinct perspectives. Proponents of libertarian ethics have criticized it as incompatible with the axiom of self-ownership and the resultant structure of natural rights. More specifically, they have pointed out that the category of property applies exclusively to scarce goods, while ideas—that is, the fruits of intellectual labor—are superabundant in virtue of their infinite replicability. Thus, forcibly restricting their replication amounts to a major act of aggression against the bodily integrity and physical property of the replicating agent (Kinsella 2008).

On the other hand, mainstream economists have demonstrated that patents and copyrights, far from promoting innovation, actually hinder economic development and Schumpeterian creative destruction. This is due to the fact that patent and copyright holders are effectively intellectual monopolists, capable of nipping in the bud the commercial development of any given idea (Boldrine and Levine 2008).

While acknowledging the validity and significance of the above criticisms, this paper offers a different take on the titular concept. Instead of suggesting that intellectual property is morally indefensible or economically harmful, it suggests that it is praxeologically impossible. In other words, this paper suggests that intellectual property laws constitute not so much an attempt at monopolizing a praxeologically distinct category of resources, but rather an arbitrary curtailment of entrepreneurial initiatives aimed at resource heterogenization. This, in turn, implies that the so-called protection of intellectual property creates not so much “intellectual monopolists,” but rather uninvited institutional co-owners (Hülsmann 2006) of their potential business competitors’ arbitrarily selected physical property.

The following section states the argument in more detail. Section 3 considers some potential counterarguments to the proposition, and section 4 concludes with a presentation of some of its further ramifications.

2. THE ARGUMENT

The fundamental insight of the marginalist-subjectivist tradition in economics is the observation that what makes a good is not its physical characteristics, but its ability to enter into causal relationships with subjective preference scales of purposive agents. Thus, even physically identical goods may differ significantly in terms of their economic value in virtue of their differing causal histories and ideational connections.

However, this crucial emphasis on the subjective nature of economic value does not change the fact that genuine economic goods, in order to qualify as such, have to exhibit objective physical scarcity. Otherwise they are not goods, but the “general conditions” of action (Rothbard 2004, 4). In other words, the marginalist-subjectivist tradition—particularly as exemplified by the Menger-Mises branch—avoids the twin pitfalls of hypersubjectivism and panphysicalism: it postulates that physically scarce objects become economic goods by being “mixed” with the ideational processes of intentional beings.

Hence, ideation turns out to be a psychological rather than a praxeological activity—in and of itself it does not fall within the purview of economic analysis, nor, by extension, within the purview of property valuation. It is only when it is translated into action that it becomes a fundamental datum of economic theory and history. And yet, as soon as it enters the realm of demonstrated preferences, it inevitably heterogenizes the resulting goods, thereby ensuring their intellectual and valuational distinctness.

This is because human action is necessarily future oriented and thus entrepreneurial in the broad sense of the term—it consists not in frictionless adjustment of supply and demand, but in the deployment of scarce means toward specific ends to be accomplished in the uncertain future (Salerno 2008). Hence, ideas, viewed as preconditions of agency, are never, strictly speaking, replicated—instead, they are adapted to one’s specific circumstances, plans, and capabilities. This, in turn, implies that as soon as a particular agent transforms particular physical objects in accordance with a given idea—even if this idea is “borrowed” from someone else—they become unique goods, infused with his unique productive touch. It should be noted here that this argument is independent of the contention that property rights apply exclusively to the physical integrity of a resource, not to its value, since the latter derives entirely from the mental states of all those individuals who are interested in putting it to some use (Hoppe and Block 2002). Although few may be willing to reject this contention in full and endorse the notion that maintaining the value of one’s resources can extend to owning others’ mental states, some may be willing to concede the inadmissibility of certain actions that diminish the value of another’s assets. Underselling the originator of a “novel product” by offering exact replicas of his merchandise could be thought of as a canonical example here. However, the argument advanced in the present paper uproots this issue entirely, since it points out that physically identical products cannot be regarded as identical in terms of the sources of their value, thus making their putative ownership and their potential positive externalities a moot point.

This observation is exceptionally striking in the context of entrepreneurship narrowly conceived—that is, in the context of exercising the ownership function over capital structures of production created and recreated under conditions of uncertainty (Foss and Klein 2012). After all, the essential determinant of the success of any given business plan is not the physical capabilities of the resources owned by a given businessman, nor even the objectively definable ideas embodied in them, but the subjective evaluation of the potential residing in these and other elements of the overall entrepreneurial vision and the corresponding capital stock (Kirzner 1997). Objectively definable inventions are technical, not economic, phenomena—it is only when they help bring about subjectively conceived innovations that they contribute to economic growth and development (McCloskey 2010). This is by no means simply a repetition of the anti-IP argument that an idea is a general prerequisite of production and not subject to ownership. It is also the realization that, as far as their productive potential is concerned, ideas implemented in concrete processes of production are entirely dissimilar to ideas conceived in abstract terms. Thus, to regard all physical objects whose creation involved some use of the fruits of one’s mental labor as falling within the ambit of one’s “intellectual property” is to commit a fundamental categorical mistake—i.e., to confuse the results of subjective plans with their objective mental preconditions.

If, on the other hand, one were to claim that it is precisely the specific conceptual content of those mental preconditions that can be subjected to intellectual property protection, then an equally flagrant categorical mistake would be made. After all, such a claim would amount to trying to obtain exclusive use not of the results of any given action, but of a necessary prerequisite of a potentially infinite range of actions. In other words, it would amount to trying to put a price tag on something that is naturally priceless—on something that is not just contingently nonscarce (as so-called free goods are), but is necessarily so (as all general conditions of action have to be).

To use a specific example, this would involve attempting to obtain exclusive use not of any particular product of, say, spelling or singing, but of the very concepts of spelling or singing. Taken to its ultimate conclusion, such an approach would paralyze all human action, destroying humankind almost on the spot by making everyone unsure of whether engaging in perfectly mundane activities violates someone else’s intellectual property rights. And if one tried to avoid this conclusion by suggesting that it is only sufficiently complex concepts that merit this kind of exclusive appropriation, one natural response would be to point out that such a suggestion smacks of sheer legalistic arbitrariness, since it has to rely on a purely discretionary standard of “sufficient complexity.” Admittedly, making it a matter of pure legal convention which ideas are subject to IP protection would not be a logically incoherent move, but it would be a move bereft of any appeal to economic justification. More specifically, it would offer no support for the claim that the purpose of licensing the use of complex concepts is to allow their authors to reap their full market value, since it would not involve laying down any precise methods of measuring the extent to which the market value of any given good derives from its embodying any such concept (Cordato 1992, 80).

Furthermore, it has to be borne in mind that all entrepreneurial activity involves resource heterogenization (Lewin and Baetjer 2011), even if it does not consist in the Schumpeterian kind of entrepreneurship, which is typically associated with the introduction of innovations and other quintessentially conceptual tasks. Hence, for instance, buying a trademarked product and simply relocating it from a relatively saturated market to a relatively unsaturated one in order to sell it at a profit suffices to create a substantially new product, associated with uniquely specific preference scales, valuational conditions, and organizational structures. In fact, in today’s age of electronic transactions an act of physical relocation is not even necessary: it suffices to engage in online arbitrage to heterogenize physically and conceptually identical goods in a productive manner. After all, if all human action is broadly entrepreneurial—that is, it requires creative confrontation with the uncertain future—then exploiting arbitrage opportunities is solidly innovative in its own right (Kirzner 2009).

In other words, even, say, using a general scientific formula in production without in any way altering it should count as an instance of adaptation rather than replication, since its successful commercialization requires integrating it with a specific, time- and space-bound capital structure of production. To repeat, ideational replication is a purely mental operation, and it is only entrepreneurial implementation of replicated ideas that can be economically meaningful in this context, since only the latter can be economically profitable or unprofitable, and thereby also more or less successful in addressing the problem of natural (i.e., nonartificial) scarcity.

Moreover, it must be stressed that the argument presented here is not reducible to the more familiar contention that ideas cannot be subject to property rights, since rights are, by definition, enforceable claims, with the “force” component tying in to the physical aspect of human control over scarce resources. Although this contention is perfectly reasonable, it does not immediately answer the objection that the originator of a certain idea may regard himself as a partial owner of all the scarce resources that in some degree embody its distinctive conceptual features. Of course, at this point one might make a solid case that the creative process, although certainly capable of increasing the value of specific goods, nevertheless does not automatically imply ownership of them, be it complete or partial. This, however, would shift the discussion to the normative level, having to do with defining the ethical or legal criteria of genuine appropriation. This argument is purely praxeological: it points out that there is no necessary valuational link between the conceptual features of ideas contemplated in abstract terms and the conceptual features of specific goods that incorporate those ideas.

In other words, the process of ideation might be thought of in terms of identifying potential profit opportunities, but from a realistically conceived entrepreneurial standpoint such opportunities are only imagined rather than discovered (Klein 2008). And since the fruits of one’s imagination can be translated into actual business ventures in an endless variety of ways, it is incoherent to claim that the value of imagined profit opportunities can be automatically imputed to their actually exploited counterparts, entitling the originators of the former to the proceeds from the latter.

In sum, the subjectivist theory of value coupled with a praxeological understanding of the market process leads to the conclusion that, economically speaking, intellectual property is a contradiction in terms. In short, ideas are not economic goods, but preconditions of action, while physical goods transformed by ideas become as heterogeneous (and thus as intellectually unique) as the individuals who enact such transformations. This, in turn, implies that as important as it is to point out the efficiency-reducing and normatively troubling consequences of so-called intellectual property protection, it is possible to raise doubts about the concept on an even more fundamental, purely logical level.

3. POTENTIAL COUNTERARGUMENTS

Let us now analyze some potential counterarguments to the suggestion advanced in the present paper.

First, it might be claimed that, regardless of one’s views on the normative aspects of the titular concept, it is an overstatement to deny its descriptive coherence. After all, one might say, it is perfectly reasonable to define the fruits of one’s intellectual labor as goal-specific technical recipes,1 readily identifiable in terms of the specific material effects that their implementation produces. This, in turn, should make it conceptually unobjectionable to designate the goods that embody such effects as bearing the marks of one’s intellectual property, even if we do not believe that such “property” is associated with enforceable natural rights or economically beneficial consequences.

The main problem with this suggestion is that, once again, it conceives of goods in technical rather than economic terms and treats ideas as if they were praxeological rather than psychological factors. Since, however, economics deals with subjective evaluations embodied in demonstrated preferences, not with scientific discoveries and their technical content, it must reject the notion that there always exists a unique, objective description of the way in which any given good can usefully incorporate a technical recipe. On the contrary, subjectivist economics, coupled with a mature theory of capital and entrepreneurship, clearly recognizes the fact that productive factors are essentially characterized in terms of their subjectively perceived attributes, functions, and uses (Foss, Foss, Klein, and Klein 2007). Hence, there is a potentially infinite number of ways in which any given technically defined object can be imbued with the fruits of entrepreneurial creativity, alertness, and foresight, thereby becoming not just conceptually novel, but also endowed with unique economic value.

Another objection that might be leveled against the titular contention is that it cannot claim universal economic validity, since it refers to a strictly normative concept (i.e., property), while economics is a positive science. Thus, one might argue, it is a category mistake to ascribe inherent incoherence to a phenomenon whose definition is ultimately a matter of legal convention or moral imagination.

The primary error of this counterargument lies in confusing the value freedom of economics with its supposed value irrelevance. Although clearly value-free as far as the contents of its theorems are concerned, economics is crucially dependent on the evaluative and normative concepts contained in its descriptions of the catallactic order (Casey 2012). For instance, the theorem of the impossibility of rational economic calculation under socialism clearly refers to the importance of certain normative institutions (private property in the means of production, free exchange of private property titles, etc.), but it does so exclusively in order to elucidate the nature of the corresponding logically necessary causal relations, without proclaiming their ethical desirability. By the same token, the theorem in question also demonstrates that certain normative visions—such as that of an economically thriving socialist commonwealth—are not so much ethically wrong as they are inherently unviable. To put it differently, ethical evaluations of intrinsically incoherent concepts are inevitably futile, since they run afoul of the principle of “ought implies can,” which often reveals such concepts to be misleading placeholders for something altogether different.

Thus, the fact that the titular contention refers to a normative concept in no way detracts from its strictly positive character. After all, it does not matter in this context whether or not one endorses the notion of intellectual property on ethical grounds—what matters is that such an endorsement cannot be couched in economically meaningful language. Consequently, the argument of this text does not violate the distinction between the positive and the normative—instead, it aims at demonstrating that it is the proponents of intellectual property who necessarily violate the distinction between the psychological and the praxeological.

At this point, one might argue that the above train of thought rests on the dubious premise that if an idea is by nature a general condition of action, this cannot be changed by legal enactment. In fact, however, no such premise is presupposed. Although it is clearly possible to legislate artificial scarcity into existence, it is impossible to ground such legislation in praxeologically meaningful facts. In other words, although it is possible to prosecute individuals or organizations for the supposed unlawful use of another’s ideas, it does not change the purely praxeological observation that anchoring any given abstract idea in the specific circumstances of one’s individual venture turns it into a fundamentally distinct idea, with no necessary valuational link between the two akin to that postulated by the Mengerian law of imputation. Hence, appealing to the conceivability of artificial scarcity in no way impugns the value freedom of this paper’s contention.

Finally, it might be suggested that the supposed economic coherence of the notion of intellectual property can be established by pointing to the specificity of the interventionist effects caused by IP protection laws. If, for instance, one subscribes to the claim that such laws hinder economic development and the corresponding creation and dissemination of innovations, then one implicitly recognizes the existence of a special category of goods whose preemptive appropriation by patent and copyright holders leads to economically suboptimal results. Thus, one might argue, intellectual property emerges as an economically meaningful concept in virtue of the economically meaningful effects of its legal enforcement.

The chief weakness of the above contention is the implicit assumption that praxeologically specific consequences must be associated with a praxeologically distinct category of goods in order to retain their analytical meaningfulness. It is the case, however, that they might as well be associated with a praxeologically distinct kind of activities. For example, in the context under consideration it might be suggested that IP protection laws hamper not so much the production and dissemination of “intellectual goods,” but the very process of heterogenization of goods—that is, the process whereby physically scarce objects become increasingly differentiated through their association with individual entrepreneurial visions. In other words, IP laws might be plausibly regarded not as a means of preemptive appropriation of “intellectual goods,” but as a tool for implementing the principles of “conservative socialism” (Hoppe 1989, chap. 5). Hence, it seems perfectly feasible to recognize the economically harmful effects of interventions aimed at the suppression of entrepreneurial utilization and reutilization of generally accessible ideas without being simultaneously committed to accepting the economic meaningfulness of the concept of intellectual property.

In sum, far from being an exaggeration, the claim that so-called intellectual property is incoherent as an economic notion appears to be a solidly justifiable proposition. Let me now conclude by briefly exploring some of its further analytical ramifications and practical implications.

4. CONCLUSION

If intellectual property is indeed a praxeologically meaningless concept, then, as proposed in the previous section, IP laws do not prevent entrepreneurs from utilizing freely a specific, precisely definable category of goods, but instead serve as a pretext for essentially arbitrary acts of opportunistic interventionism. This indicates that they are far more capable of paralyzing the operation of the market process than is suggested by the traditional arguments centered on the economically stifling influence of “intellectual monopolies.” More concretely, IP laws’ definitional arbitrariness appears particularly capable of saddling entrepreneurs with a highly troublesome layer of regime uncertainty (Higgs 1997), which does not generate additional (though predictable) costs for entrepreneurial activity so much as it makes such activity essentially unpredictable on the institutional level (Kinsella 1995, 150–51).

Furthermore, the laws in question are especially likely to cripple the operations of specifically “Schumpeterian” firms (Mueller 2003, chap. 4), that is, those that rely exceptionally heavily on creating value through resource heterogenization based on ingenious adaptation of existing technical recipes. Such firms, which are typically at the forefront of robust economic development, are especially exposed to the arbitrary interventionism of the established players, who are constantly on the lookout for excuses to accuse the newcomers of “intellectual free riding.” In addition, this kind of environment gives the management of Schumpeterian firms an extra incentive to join the establishment’s interventionist game as soon as possible, thereby perpetuating and further strengthening the vicious circle of rent seeking, cronyism, and enforced economic petrification.

Finally, the unhampered entrepreneurial transformation of various technical concepts is a phenomenon whose continuation is particularly important to a globally interconnected and organizationally complex society. If such a society suddenly becomes irresponsive to the economic challenges continually generated by its dynamically changing environment, which is bound to happen under conditions of repressed resource heterogenization, it will fall victim to institutional fragility (Taleb 2012) and become incapable of sustaining its complexity, ultimately collapsing under its own weight.

In conclusion, since intellectual property is a praxeologically incoherent term, IP laws turn out to constitute an exceptionally arbitrary and thus exceptionally disruptive form of interventionism directed against the very essence of the entrepreneurial market process (Kirzner 2017). Hence, intellectual property laws should be viewed as an even more fundamental obstacle to robust economic development than has been suggested by hitherto prevailing arguments.

- 1. For the purpose of this paper, the terms “recipe,” “idea,” and “concept” are treated as interchangeable.

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoBernice King, Ava DuVernay reflect on the legacy of John Lewis

-

World News2 weeks ago

Heavy rain threatens flood-weary Japan, Korean Peninsula

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoEverything New On Netflix This Weekend: July 25, 2020

-

Finance3 months ago

Will Equal Weighted Index Funds Outperform Their Benchmark Indexes?

-

Marketing Strategies7 months ago

Top 20 Workers’ Compensation Law Blogs & Websites To Follow in 2020

-

World News7 months ago

World News7 months agoThe West Blames the Wuhan Coronavirus on China’s Love of Eating Wild Animals. The Truth Is More Complex

-

Economy9 months ago

Newsletter: Jobs, Consumers and Wages

-

Finance8 months ago

Finance8 months ago$95 Grocery Budget + Weekly Menu Plan for 8