Economy

Newsletter: Jobs, Consumers and Wages

This is the web version of the WSJ’s newsletter on the economy. You can sign up for daily delivery here.

It’s jobs day! Economists are forecasting a net gain of 75,000 for U.S. payrolls in October and a slight bump in the unemployment rate to 3.6%. Wildcards: The United Auto Workers strike at General Motors and Census Bureau hiring could muddy the the numbers. Here’s what to watch.

And now for today’s key economic themes…

Consumers Gonna Consume

U.S. households increased spending heading into the fourth quarter, suggesting consumers have continued to prop up economic growth. Personal-consumption expenditures rose a seasonally adjusted 0.2% in September from the prior month, same as August. Outlays had grown more briskly in the first half of 2019, Sarah Chaney and Paul Kiernan report.

- Consumers are helping lift the economy while manufacturing and business investment falter. They are, however, spending at a less robust pace than last year, aligning with a broader slowdown in economic growth that economists expect to continue.

- The economy grew at a 3.1% pace in the first quarter of the year, 2% in the second and 1.9% in the third. Though very preliminary, forecasters at Macroeconomic Advisers are tracking fourth-quarter growth at 1.7%.

WHAT TO WATCH TODAY

U.S. nonfarm payrolls for October are expected to increase by 75,000 from the prior month and the unemployment rate is expected to tick up to 3.6%. (8:30 a.m. ET)

IHS Markit’s U.S. manufacturing index for October is expected to hold steady at 51.5. (9:45 a.m. ET)

The Institute for Supply Management’s manufacturing index for October is expected to rise to 49.1 from 47.8 a month earlier. (10 a.m. ET)

U.S. construction spending for September is expected to increase 0.2% from the prior month. (10 a.m. ET)

The Baker Hughes rig count is out at 1 p.m. ET.

The Dallas Fed’s Robert Kaplan participates in a moderated Q&A at 9:30 a.m. ET, the New York Fed’s John Williams speaks in Newark, N.J., at noon and again at 2:30 p.m. ET, Vice Chairman Richard Clarida speaks at a Japan Society Special Luncheon at 1 p.m. ET, and Vice Chairman Randal Quarles speaks about Friedrich Hayek and the price system at 1 p.m. ET.

TOP STORIES

No Smoke, No Heat

Have wage gains topped out for this expansion? The employment cost index, a favorite measure at the Federal Reserve, shows wage and salary pressure is modest and apparently not building—despite an unemployment rate at a 50-year low.

- For private-sector workers, third-quarter wages and salaries advanced 3% from a year earlier for the third straight quarter. They had been rising 3.1% in the latter half of 2018.

- That mirrors other indicators. Average hourly earnings and a measure of small business plans to raise wages have both come off of recent peaks.

- Economists are forecasting a 3% annual gain for average hourly earnings in October, a small pickup from September but still well below the 3.4% gain workers enjoyed in February.

“The tame momentum in compensation growth, along with the moderation in other wage metrics in recent months, suggests that wage growth has likely reached a cycle peak,” says Oxford Economics economist Kathy Bostjancic.

- Good news: Weaker wage pressures could keep inflation in check, giving the Fed plenty of leeway to keep rates low.

- Bad news: Slower wage gains could cap consumer spending, the main driver of economic growth in recent quarters.

Looking for Inflation

U.S. inflation remained soft in September. The Fed’s preferred gauge, the personal-consumption expenditures price index, fell a seasonally adjusted 0.01% last month from August, its weakest monthly reading since January. From a year earlier, the index was up 1.33%. An index of so-called core prices, which excludes volatile food and energy components, rose 1.67% on the year. The data suggest a pickup in prices over the summer may have been short-lived. Inflation continues to run lower than the Fed’s 2% target—and officials remain concerned about the risk of falling prices in a downturn, Paul Kiernan and Sarah Chaney report.

Phase 1

President Trump said China and the U.S. are in the process of selecting a new site to sign “phase one” of a trade agreement between the two countries. Mr. Trump had hoped to ink the deal during a November Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Chile, but Chilean President Sebastian Piñera canceled the gathering amid widening protests, Andrew Restuccia reports.

Factory Ups and Downs

A private gauge of China’s factory activity showed an expansion for the third straight month in October. The Caixin China manufacturing purchasing managers index rose to a 32-month high of 51.7, above the 50 mark that separates expansion from contraction and contrasting with the official gauge showing a fall in activity for the sixth consecutive month. Elsewhere in the world, factory figures were more bleak: Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan and Malaysia each reported contractions in activity. India’s manufacturing sector grew, but at the weakest pace in two years.

Demographics, Destiny and China

China has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world, and recent data suggest its demographic bind is even more serious than thought. In 1970, China’s median age was nearly 10 years below that of the U.S. By 2015, it was higher. The prospect of fewer and fewer workers to support retirees amid a rising median age is looming large over the Chinese economy. Nonetheless, birth limits remain in place. Couples are now allowed to have two children, but not more than that—despite the birth numbers and government expectations that the population will start to decline in 2030, Liyan Qi and Fanfan Wang report.

Charm Offensive

Christine Lagarde takes over as president of the European Central Bank today. The 63-year-old Frenchwoman will have to break a deadlock among eurozone policy makers over how to support the region’s faltering economy. In the days before assuming the presidency, Ms. Lagarde gave a hint of how she will seek consensus. A rash of interviews—including one in which she explicitly criticized President Trump—and a charm offensive in Germany, the ECB’s biggest critic, could presage a very different style from outgoing President Mario Draghi, a veteran central banker who communicated through carefully controlled speeches and news conferences, Tom Fairless reports.

WHAT ELSE WE’RE READING

That third kid, woah. “A third birth induced by a twin birth or the same-sex composition of the first two children or twin birth at the second parity increases the probability of alcohol consumption by about 5.0 percentage points. Both on the extensive and intensive margins, a larger family size also leads to a substantial increase in maternal binge drinking,” Clemson University’s Sarah Wilson writes in a job market paper.

After the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident in Japan, nuclear power stations were closed and nuclear power was replaced by fossil fuels. That cause higher energy prices, less energy consumption and a more deaths during cold spells. “We estimate that the increase in mortality from higher electricity prices outnumbers the mortality from the accident itself, suggesting the decision to cease nuclear production has contributed to more deaths than the accident itself,” Matthew Neidell, Shinsuke Uchida and Marcella Veronesi write in a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper.

SIGN UP FOR OUR CALENDAR

Real Time Economics has launched a downloadable calendar with concise previews, forecasts and analysis of major U.S. data releases. To add to your calendar, please click here.

Economy

Dorothy Theresa Sawchak Mankiw

Above is a picture of my mother as a young woman. I would like to tell you about her.

My mother was born on July 18, 2020, the second child of Nicholas and Catherine Sawchak.

Nicholas and Catherine were immigrants from Ukraine. They came to the United States as teenagers, arriving separately, neither with more than a fourth-grade education. Catherine was from a farming area in western Ukraine. She left because her family wanted her to marry an older man rather than her younger boyfriend, who had been conscripted into the army. Her first job here was as a maid. Nicholas was from Kiev, where he had been trained to be a furrier. In the United States, he worked as a potter, making sinks and toilettes. When Nicholas and Catherine came to the United States, they thought they might return home to Ukraine eventually. But World War I and the Russian Revolution intervened, causing a change of plans. Catherine’s boyfriend died in the war. Nicholas and Catherine met each other, married, and settled in a small row house in Trenton, New Jersey, where they lived the rest of their lives.

Catherine and Nicholas had two children, my uncle Walter and my mother Dorothy. When my mother was born, her parents chose to name her “Dorothy Theresa Sawchak.” But because Catherine spoke with a heavy accent, the clerk preparing the birth certificate did not understand her. So officially, my mother’s middle name was “Tessie” rather than “Theresa.” She never bothered to change it.

Nicholas and Catherine were hardworking and frugal. They saved enough to send Walter to college and medical school. He served as a physician in the army during the Korean war. Once I asked him if he worked at a MASH unit, like in the TV show. He said no, he worked closer to the front. He patched up the wounded soldiers the best he could and then sent them to a MASH unit to recover and receive more treatment. After the war, he became a pathologist in a Trenton-area hospital. He married and had two daughters, my cousins.

My mother attended Trenton High School (the same high school, I learned years later, attended by the economist Robert Solow at about the same time). She danced ballet. She water-skied on the Delaware River. She loved to read and go to the movies.

In part because of limited resources and in part because of the gender bias of the time, my mother was not given the chance to go to college. Years later, her parents would say that not giving her that opportunity was one of their great regrets. Instead, my mother learned to be a hairdresser. She was also pressured to marry the son of some family friends.

The marriage did not work. With my mother pregnant, her new husband started “running around,” my mother’s euphemism for infidelity. They divorced, and she kicked him out of her life. But the marriage did leave her with one blessing—my sister Peg.

My mother continued life as a single mother. Some years later, she met my father, also named Nicholas, through social functions run by local Ukrainian churches. They both loved to dance. He wanted to marry her, but having been burned once, she was reluctant at first. Only when she realized that he had become her best friend did she finally accept.

In 1958, nine months after I was born, Mom, Dad, Peg, and I left Trenton for a newly built split-level house in Cranford, New Jersey. My father was working for Western Electric, an arm of AT&T, first as a draftsman and then as an electrical engineer. He worked there until his retirement. One of his specialties was battery design. When I was growing up, I thought it sounded incredibly boring. Now I realize how important it is.

My mother then stopped working as a hairdresser to become a full-time mom. But she kept all the hairdresser equipment from her shop—chair, mirrors, scissors, razors, and so on—in our basement. She would cut the hair of her friends on a part-time basis. When I was a small boy, she cut my hair as well.

I attended the Brookside School, the public grade school which was a short walk from our house. When I was in the second or third grade, my mother was called in to see the teacher. The class had been given some standardized aptitude test. “Greg did well,” the teacher said. “We were very surprised.”

At that moment, my mother decided the school was not working out for me. I was talkative and inquisitive at home but shy and lackluster at school. I needed a change.

She started looking around for the best school she could find for me. She decided it was The Pingry School, an independent day school about a dozen miles from our house. She had me apply, and I was accepted.

The question then became, how to pay for it? Pingry was expensive, and we did not have a lot of extra money. My mother decided that she needed to return to work.

She started looking for a job, and an extraordinary opportunity presented itself. Union County, where we lived, was opening a public vocational school, and they were looking for teachers. She applied to be the cosmetology teacher and was hired.

There was, however, a glitch. The teachers, even though teaching trades like hairdressing, needed teacher certification. That required a certain number of college courses, and my mother had not taken any. So she got a temporary reprieve from the requirement. While teaching at the vocational school during the day, she started taking college courses at night to earn her certification, all while raising two children.

My mother taught at the vocational school until her retirement. During that time, she also co-authored a couple of books, called Beauty Culture I and II, which were teacher’s guides. From the summary of the first volume: “The syllabus is divided into six sections and includes the following areas of instruction: shop, school, and the cosmetologist; sterilization practices in the beauty salon; scalp and hair applications and shampooing; hair styling; manicuring; and hairpressing and iron curling.” I suppose one might view this project as a harbinger of my career as a textbook author.

When my parents both retired, they were still the best of friends. They traveled together, exploring the world in ways that were impossible when they were younger and poorer. During my third year as an economics professor, I was visiting the LSE for about a month. I encouraged my parents to come over to London for a week or so. They had a grand time. I believe it was the first time they had ever visited Europe. When I was growing up, vacations were usually at the Jersey shore.

My father died a few years later. My mother spent the next three decades living alone. She was then living full-time at the Jersey shore in Brant Beach on Long Beach Island. The house was close to the ocean and large enough to encourage her growing family to come for extended visits. Two children, five grandchildren, four great-grandchildren. The more, the merrier. Nothing made her happier than being surrounded by family.

My mother loved to cook, especially the Ukrainian dishes she learned in her childhood. Holubtsi (stuffed cabbage) was a specialty. Another was kapusta (cabbage) soup. One time, the local newspaper offered to publish her kapusta soup recipe. They did so, but with an error. Every seasoning that was supposed to be measured in teaspoons was printed as tablespoons. The paper later ran a correction but probably to no avail. I am not sure if anyone ever tried the misprinted recipe and, if so, to what end.

During her free time in her later years, my mother read extensively, played FreeCell on her computer, and watched TV. A few years ago, when she was about 90 years old, I was visiting her, and I happened to mention the show “Breaking Bad.” She had not heard of it. She suggested we watch the first episode. And then another. And another. After I left, she binge-watched all five seasons.

As she aged, living alone became harder. When she had trouble going up and down the stairs, an elevator was added to her house. But slowly her balance faltered, and she fell several times. She started having small strokes, and then a more significant one. She moved into a nursing home. Whenever I visited, I brought her new books to read. Her love of reading never diminished.

This is, I am afraid, where the story ends. Last week, Dorothy Theresa Sawchak Mankiw tested positive for Covid-19. Yesterday, she died. I will miss her.

Source link

Economy

The GDP Collapse: It Is What It Is

Jim discussed elements of the 2020Q2 advance release on Thursday. Here, I amplify some aspects that he mentioned.

Confirmation: A Catastrophe in the Making

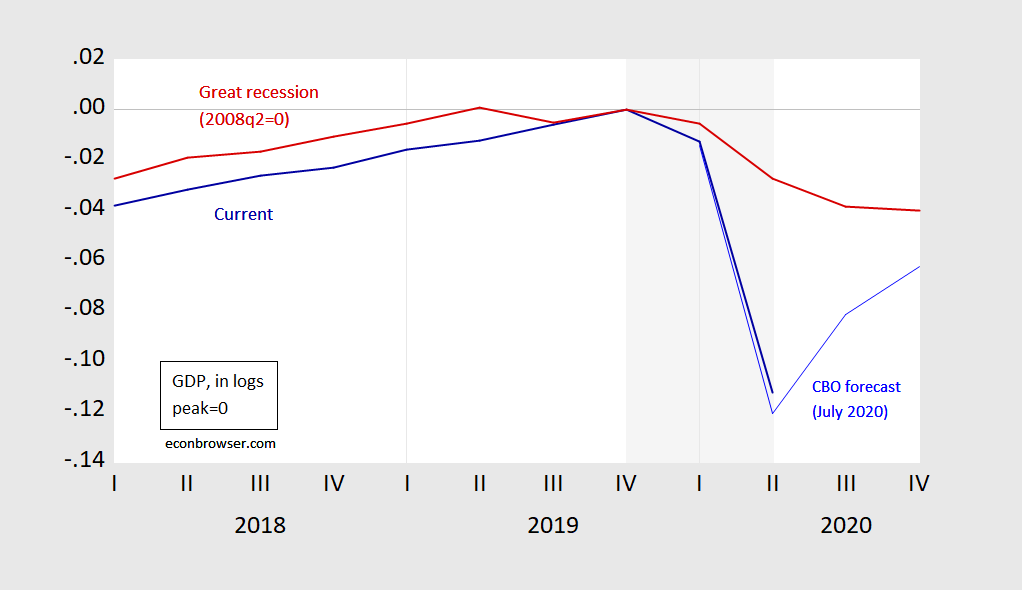

First, the Trump recession is truly catastrophic in scale; the pace of GDP decline is much greater than that in 2008. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: GDP in logs, normalized to 0 at 2019Q4 (NBER peak) (blue), and GDP normalized to 2008Q2 (red). NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming trough at 2020Q2. Source: BEA, 2020Q2 advance release, NBER, author’s calculations.

A “No Confidence” Vote in Administration Policy and Investment

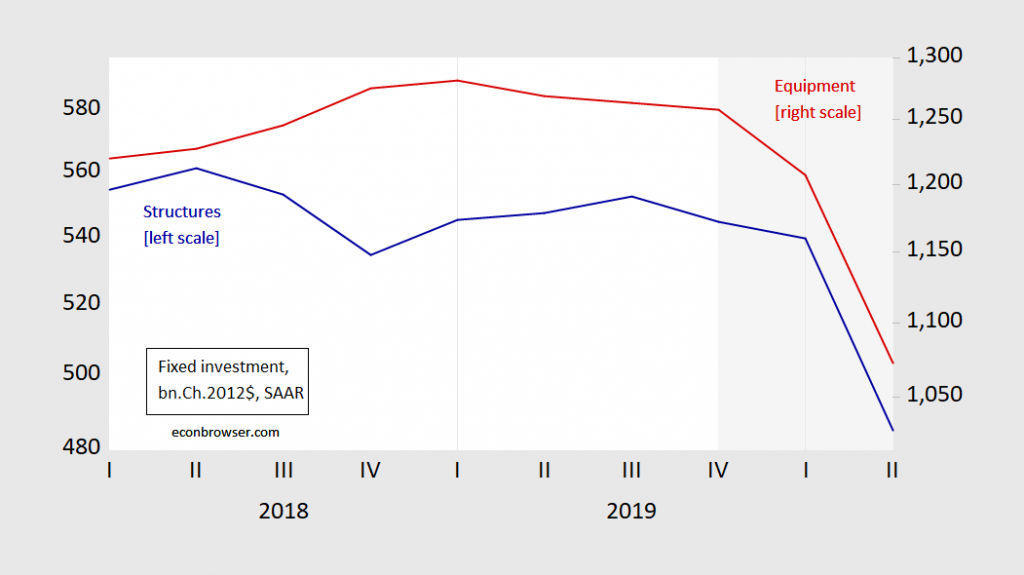

Second, investment has crashed — for both structures and equipment investment. That’significant insofar as capital investment is forward looking.

Figure 2: Fixed investment in structures (blue, left log scale), and in equipment (red, right log scale), in billions Chained 2012$, SAAR. NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming trough at 2020Q2. Source: BEA, 2020Q2 advance release, NBER, author’s calculations.

This decline is even more rapid than in 2008Q4; 31.5% now vs. 24% then.

Figure 3: Nonresidential fixed investment in logs, normalized to 0 in 2019Q4 (blue), and normalized to 0 in 2008Q2 (red). NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming trough at 2020Q2. Source: BEA, 2020Q2 advance release, NBER, author’s calculations.

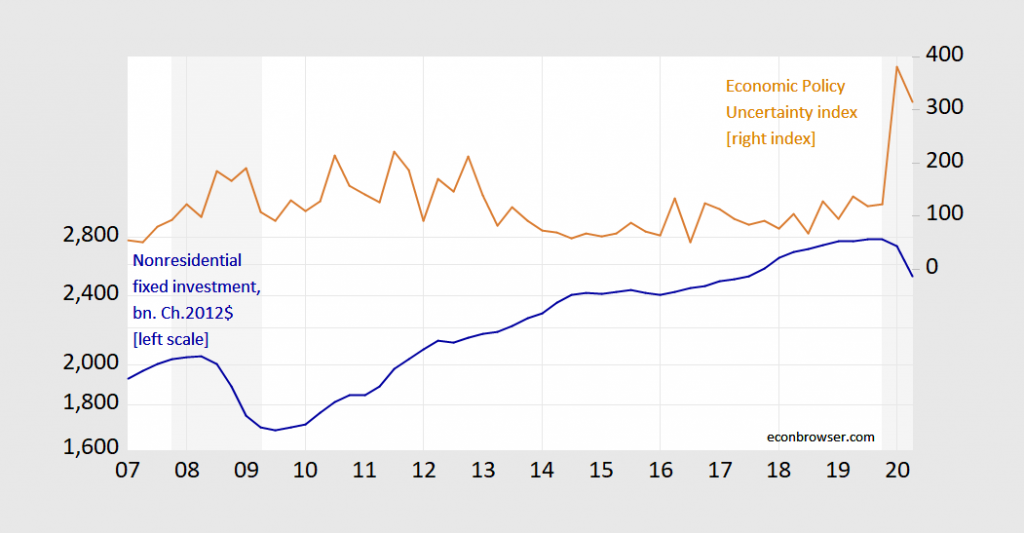

Certainly, some of the crash is due to the crash in aggregate demand — as in the 2007 recession — but some is due to uncertainty, including policy uncertainty. Policy uncertainty levels currently dwarf those of the Great Recession.

Figure 4: Nonresidential fixed investment in billions Chained 2012$ SAAR (blue, left log scale), Economic Policy Uncertainty index (tan, right scale). NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming trough at 2020Q2. Source: BEA, 2020Q2 advance release, NBER, policyuncertainty.com via FRED, and author’s calculations.

No Recovery Without Recovery in Services Demand

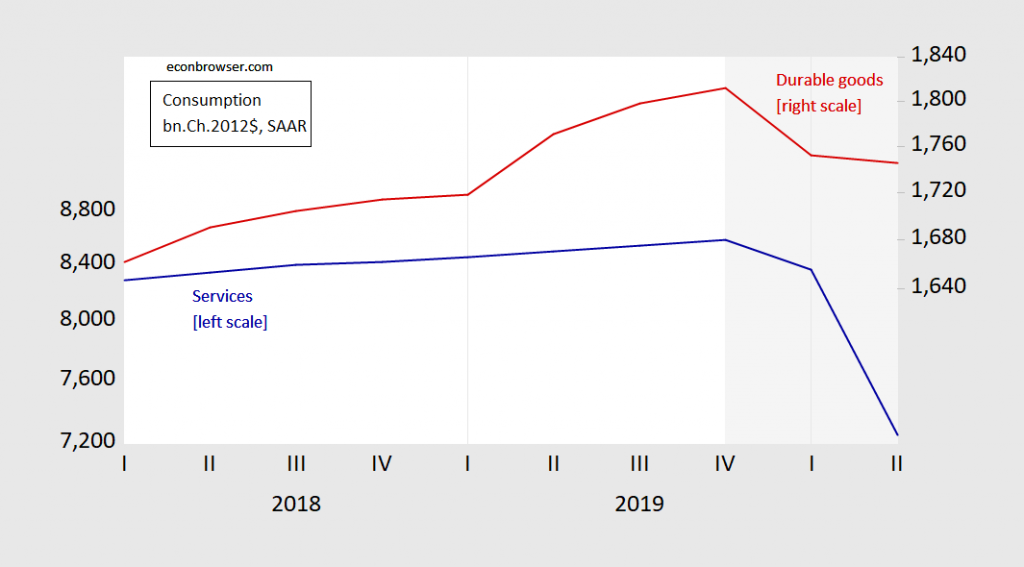

Third, this is a different kind of recession, in many ways, but importantly in the sectoral origin. As Jim Hamilton noted, the decline in services consumption was 43.5% on an annualized basis, while durable goods consumption was relatively flat.

Figure 5: Services consumption (blue, left log scale), and durable goods consumption (red, right log scale), all in billions Chained 2012$ SAAR. NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming trough at 2020Q2. Source: BEA, 2020Q2 advance release, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Of the 9.8 percentage point decline in GDP (not annualized), 5.9 percentage points were accounted for (in a mechanical sense) by services consumption decline. Jim provides a breakdown of the services consumption decline in his post.

Services consumption will not fully recover until such time as the Covid-19 infection rates are at manageable levels that do not deter such consumption activities. The Administration’s current policy stance is unlikely to encourage that development; one could argue that it — in toto — is impeding that outcome.

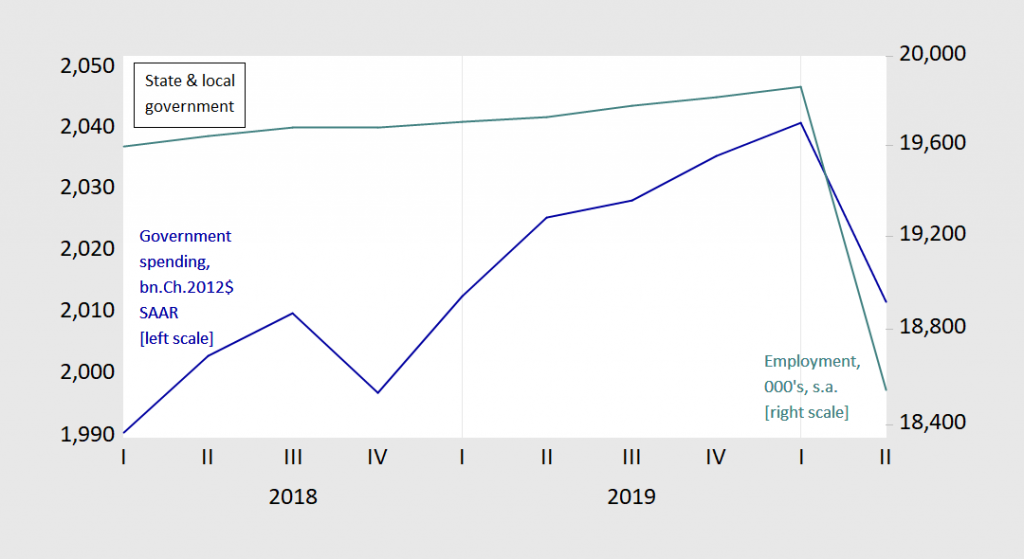

State and Local Government Spending Collapses

Fourth, the biggest threat to the economy may be avoidable. One of the lessons of the Great Recession is that constraints on state and local government spending — exacerbated by ill-advised state income tax cuts — was one of the reasons for the torpid pace of recovery. So far, we have not replicated completely that experience, but with Republican opposition to further Federal transfers to the state, we are in danger of repeating that error.

Figure 6: State and local government spending, billions Chained 2012$ SAAR (blue, left log scale), and state and local employment, 000’s, s.a. (teal, right log scale). Source: BEA 2020Q2 advance release, BLS employment situation June release.

This is why it is critical, as many economists have argued, for the next recovery package to include substantial aid to the states and localities.

Economy

The Big Tech Hearings Could Be a Model for Corporate Accountability

The American Prospect

In 2018, Democrats ran and won on a platform to hold President Trump and his cronies accountable. Many observers expected to be treated to a full schedule of oversight programming in the succeeding Congress, with a nearly endless stream of smug incompetents being caught in their lies and obfuscations. Some even dared to hope that the oversight fervor might spill over to another breed of smug incompetents: corporate CEOs. But, alas, the promised enthusiasm for oversight never seemed to materialize, let alone spread to new targets. (As usual, House Financial Services Committee chairwoman Maxine Waters, who confronted big bank CEOs within months of assuming control of her committee, stands out as a rare exception).

This general dearth of accountability made the House Judiciary Antitrust Subcommittee’s hearings last week with Big Tech CEOs all the more refreshing. Through incisive questioning, lawmakers were able to coax out consequential admissions of wrongdoing and bring to public attention the myriad harms these companies have perpetrated and then worked hard to obscure. Perhaps most critically, the information they uncovered and put into the public record lays a solid foundation for future legislative and executive action.

Arguably just as important as the policy substance, however, is the fact that the hearings were engaging and frankly satisfying to watch. As they have grown more powerful, the Big Four tech firms have slipped further and further from the grip of democratic accountability. Like private governments, they have set rules that dictate the terms of the livelihoods, social engagements, and media consumption of billions of people around the globe. But as much as they like to pretend to be sovereigns, Big Tech companies are ultimately subject to the rules and regulations our government democratically (at least in theory) sets forth. It’s good to see them reminded of that fact periodically.

As inspiring as the hearings were, however, they were also frustrating, as they begged the question: Why stop with Big Tech? Although Silicon Valley giants may be the most widely-recognized examples of corporate power run amok, they are far from the only ones. In other words, last Wednesday’s success can and should be widely replicated.

The possibilities are endless, and potentially overwhelming. Given the current crisis, committees would be well-advised to start by challenging the corporate giants who have made the pandemic worse.

As they have grown more powerful, the Big Four tech firms have slipped further and further from the grip of democratic accountability.

That includes the private equity firms whose mismanagement of nursing home conglomerates left them particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 outbreaks. In their heartless pursuit of profits, private equity firms loaded the nursing homes under their control with unsustainable debt, forcing them to cut staff, cut pay, and cut corners. Even before the pandemic, researchers documented how this led to worse outcomes and higher fatalities for patients in private equity-backed homes. And when COVID-19 hit, these facilities were particularly ill-prepared to respond.

The House Ways and Means Committee should make the heads of these private equity firms—behemoths like Carlyle Group, Blackstone, and Warburg Pincus—answer for their actions. With jurisdiction over the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which sets standards of care for nursing facilities, Ways and Means is well-positioned to not only get answers, but ensure that those answers lead to action.

Many of these same private equity titans are long overdue for an appearance before the Energy and Commerce Committee as well. When they weren’t snapping up nursing home chains, private equity firms were quietly constructing an empire of hospital chains. Just as with long-term care facilities, the aggressive pursuit of profit and mounds of debt left hospitals with little cushion to absorb unexpected blows. Sure enough, when the pandemic put lucrative elective surgeries on hold, some private equity-backed hospitals were quick to crumble. At least one leveraged its collapse into a bailout, holding healthcare amid a pandemic hostage in exchange for relief.

Given these and other bad outcomes, it’s time that Energy and Commerce put private equity CEOs under the microscope and consider the implications for the agencies under its jurisdiction like the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Health and Human Services.

Meanwhile, the Education and Labor committee would do well to put another set of corporate villains—meatpacking companies—in the hot seat. Meatpacking plants quickly became coronavirus hotspots in the U.S. The experience in other countries shows that this was not just an inevitable function of poor working conditions, but a result of distinct choices from meatpacking companies and policymakers. Rather than working to protect their employees, meatpackers turned their attention to warding off health officials and regulation. That choice has had fatal consequences and they should be asked to account for it. A close examination of the breakdowns in the enforcement of occupational safety standards and the processes by which regulators are supposed to respond in an emergency, will also be a prerequisite to getting the response better next time.

Moreover, meatpackers appear to have claimed shortages in product from their plants as a pretense to charge groceries more for beef and pork, which resulted in higher prices for consumers. Yet at the same time, these companies were shipping record amounts of meat abroad, suggesting that they were creating the shortages themselves, and pocketing the profits. The Education and Labor Committee could join Sens. Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) in exploring that as well.

Furthermore, to the extent that all of these industries are highly concentrated, the House Antitrust Subcommittee itself could haul in these corporate leaders to ask them about their businesses. Big Tech isn’t the only industry requiring a second look through an antitrust lens.

As the success of last week’s hearing makes clear, House Democrats’ choice to largely spurn corporate oversight has been a big missed opportunity. Confrontations with the country’s ever more powerful corporate giants not only make for good policy but also good politics. If House Democrats are serious about either, they will fill the coming months with such clashes.

The post The Big Tech Hearings Could Be a Model for Corporate Accountability appeared first on Center for Economic and Policy Research.

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoBernice King, Ava DuVernay reflect on the legacy of John Lewis

-

World News2 weeks ago

Heavy rain threatens flood-weary Japan, Korean Peninsula

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoEverything New On Netflix This Weekend: July 25, 2020

-

Finance3 months ago

Will Equal Weighted Index Funds Outperform Their Benchmark Indexes?

-

Marketing Strategies7 months ago

Top 20 Workers’ Compensation Law Blogs & Websites To Follow in 2020

-

World News7 months ago

World News7 months agoThe West Blames the Wuhan Coronavirus on China’s Love of Eating Wild Animals. The Truth Is More Complex

-

Finance8 months ago

Finance8 months ago$95 Grocery Budget + Weekly Menu Plan for 8

-

Technology8 months ago

Walmart’s ‘Daily Deal Drop’ sale is just as good as Black Friday – here are today’s 10 best deals